Why Did San José Really Lose 400 Police Officers?

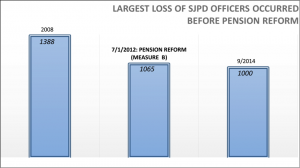

The number of sworn officers in the San José Police Department has dropped from 1388 prior to the Great Recession, to approximately 995 today.1 Much has been made by the Cortese campaign and police union that “pension reform drove officers away.” Of course, it has not helped that the same police union bosses that have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to elect Cortese have also engaged in a pattern of encouraging officers to leave San José to support their political argument that their pensions and benefits shouldn’t be reduced. They’ve invited other cities’ recruiters to the San José police union hall, and by discouraging new recruits, such as one recruit who recently wrote an op-ed in the Mercury News.

There’s no question that some officers found better pay and benefits elsewhere, and that prompted their decisions to leave. But the facts tell us far more: that over 80% of the reduction in the police force occurred for a different reason: the City ran out of money.

How do we know? Because the police department had lost 323 officers before the pension reform measure, Measure B, was ever enacted. That is, by the time that Measure B was passed in June 2012, and became effective three weeks later, San Jose Police Department had only 1065 sworn officers.

So, why did the Department lose over 323 officers before pension reform? Simply, the City couldn’t afford to pay officers to work, because it paid them so well to retire. The City experienced a decade of chronic budget deficits, and in the worst years of the great recession, those deficits exceeded $100 million annually. We had layoffs, hiring freezes, and agreed-upon pay cuts to avoid even more severe layoffs.

So, why did the Department lose over 323 officers before pension reform? Simply, the City couldn’t afford to pay officers to work, because it paid them so well to retire. The City experienced a decade of chronic budget deficits, and in the worst years of the great recession, those deficits exceeded $100 million annually. We had layoffs, hiring freezes, and agreed-upon pay cuts to avoid even more severe layoffs.

Why such large deficits? Throughout that time, retirement costs skyrocketed, quintupling in a decade from approximately $60 million annually to $310 million today, to pay long-overdue costs on a rapidly rising unfunded retirement debt. While Dave Cortese and his council colleagues voted seven times for larger pension and retirement benefits during his term on the Council, we saw unfunded retirement debts exceed $3 billion ( yes, “billion” with a “b”!)

How did they get to such large unfunded debts? Here’s a simple explanation: officers in the last half decade were retiring at age 52 or 53 with pensions of an average of over $104,000 in the first year of retirement. Due to a 3% cost-of-living adjustment, that average pension will increase to over $200,000 by the time that the officer reaches his 70s. Of course, that doesn’t count the cost for free health insurance, sick-leave payouts or other expensive benefits. Simply, the math never worked. Cortese and the police union bosses who supported these increases never bothered to identify the money to actually pay for these very generous benefits.

As a result, the City ran out of money, and our neighborhoods ran out of officers. That’s why Sam Liccardo pushed for pension reform in 2012, and why Sam put a plan together last year that identified over $35 milliion in reform savings to accelerate hiring and restore pay to improve police retention. That’s a critical issue in this election: how we can restore the police department, and improve safety—and still pay for it.

1. Unlike the Cortese campaign, which compares “apples” and “oranges” to present a more drastic picture of the officer losses, for example by including injured officers in the “before” count and excluding them in the “after,” we use the same metrics for before and after, namely, the actual number of sworn police officers. We follow the same approach used by the SJPD and the City’s Human Resources Department.