Our Safety

How can a Mayor better support our officers’ good work in battling crime in the city and restore our sense of safety? Below you’ll find ten elements of a strategy to restore San José’s prominence as America’s safest big city.

Plenty has been written and said about the need to add more police officers, but I worked with Mayor Reed to actually craft a strategy to do so. We obtained Council approval of that plan in the Fall of 2013, and we’ve begun implementation.

For reasons we’ll explore shortly, however, restoring public safety in San José will require far more than merely adding officers to our ranks. Adding officers will require tens of millions of dollars of ongoing funding, and several years of recruiting, screening, hiring, instruction and training before enough officers will be street-ready.

The real question, then, is what will we do in the meantime? That is, while we’re finding the money, assembling the resources and completing the hiring and training, what do we do to address crime?

We’ll need to be smarter, more efficient and more innovative. This requires going beyond bumper sticker solutions that merely fan the emotional flames around crime, and focusing on how we can more effectively leverage the resources we do have. Here’s an outline of my plan, with hyperlinks that explain each proposal in greater detail for those who want a “deeper dive”:

1. Hire More Cops

Restoring the numbers of our sworn officers will certainly help. I’ve led an initiative to add over 200 police officers within four years. The Mayor and Council overwhelmingly approved that plan in October of 2013, and we have begun implementation. As we hire more officers, we must impose repayment obligations on those cities that hire away our young officers where San José has footed the bill for their academy education and training.

2. Leveraging “Force Multiplying” Technology and Approaches to Support Our Officers

We have seen evidence that data analytics, body-worn cameras, crowd-sourcing of video, social media, and other tools can enable police departments to better deploy their officers, collect evidence, and anticipate crime. As Silicon Valley’s urban center, San José must invest in and employ innovative crime-fighting technologies. We can also deploy the varying skill levels of our workforce more strategically. Using more trained civilian “Community Service Officers” to perform simple tasks—such as taking statements of burglary victims or lifting fingerprints–can enable our patrol officers and detectives to re-focus their time on their higher-skill responsibilities and rebuild our investigative units.

3. Addressing Gang Violence

We can improve our response to gang crime by retaining gang detectives in the Gang Investigations Unit for a longer period than the current three years, to better benefit from their experience and expertise. We can also rely more effectively on partnerships: engaging with the District Attorney to implement gang injunctions, and teaming up with the school districts to expand truancy abatement. Finally, I will support and encourage promising approaches to boost job opportunities for at-risk teens.

4. Restoring “Community Policing”

To be effective, patrol officers must build trust and familiarity with a community to encourage residents to report crime, volunteer information, and participate in anti-crime efforts. We can improve the relationships of our patrol officers with community members by eliminating the existing 6-month rotations that interrupt the crucial relationship-building, and by making compensated bilingual education a mandatory part of training. Finally, expanding Crisis Intervention Training, necessary for interacting with mentally ill individuals, can reduce violent arrests and build community trust.

5. “Bowling Together”: Helping Communities Take Back Their Streets By Building Social Capital

Building relationships within communities can have some powerful impacts, and as studies show, reducing crime is one of them. City Hall can help, sometimes by engaging residents more meaningfully, and sometimes simply by getting out of the way of grassroots efforts to build community.

6. Regionalizing Crime-Fighting

Crooks don’t confine their activities within strict jurisdictional city boundaries. Policing and investigations shouldn’t, either. Borrowing from our regional auto theft task force, we should formalize partnerships with nearby cities and the Sheriff to battle burglaries, streetlight-disabling wire theft, prostitution, and other crimes.

7. Gambling, Booze and Weed: Common-Sense Approaches to Businesses That Impact Our Quality Of Life

Perfectly legal businesses–even when well-managed by reputable ownership–can have widespread crime-inducing impacts on a community. At a time when police remain so thinly-staffed, we need to do what we can to support our neighborhoods and quality of life with sensible regulation. That includes holding the line on card club expansion, halting the proliferation of marijuana dispensaries and corner liquor stores, and incentivizing the conversion of those stores to more neighborhood-friendly retail.

8. Reducing Crime by Improving the Streetscape

The built environment has an impact on crime–and on our sense of safety–in our business districts, parks, and neighborhoods. Encouraging development that brings “eyes out to the street,” improves lighting, and other enhancements can go a long way to supporting a safer San José.

9. The Hidden Crime: Battling Domestic Violence

The most lethal period in the cycle of domestic violence occurs when the victim makes her first attempts to leave the batterer, and to report the abuse to the police. By improving access to victim services, transitional housing, and with better coordination between police and service providers, we can greatly impact safety at that critical moment.

10. Improving Emergency Medical Response

As our over-70, over-80, and over-90 population surges in the coming decade, we need to better prepare our emergency medical response efforts to meet a likely surge in use. Our next Mayor must focus on improving our ability to provide emergency medical response to our communities and deploy strategies that reflect our current and future needs.

1. Hire More Cops

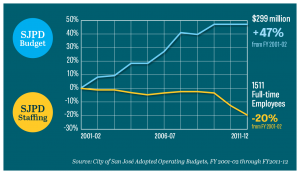

Nobody doubts that we should do all that we can to bolster the size of our police force and give our hard-working officers relief with additional patrol officers. In the wake of budget cuts, hiring freezes, pay cuts, and benefit reductions, our ranks have shrunk by almost 400 officers since 2008.

Some have sought to blame pension reform for the staffing shortfalls in our police department. It’s true that our ranks were dropped from 1,065 to 1,023 officers in the two years since the implementation of the pension reform initiative Measure B, a net loss of 42 officers, as new hires offset some officers who have left.

Yet compare that net loss of 42 officers since pension reform to what occurred in the four years prior to Measure B’s passage: a net loss of 323 officers.

Why did we lose so many officers before the passage of pension reform? For the same reason why I — and almost 70% of San José voters — supported pension reform: the City ran out of money. Annual costs for retirement benefits — spurred by a $3 billion debt in those pension accounts — skyrocketed; by 2013, the City was paying $200 million more for annual retirement benefits than the decade before. Consecutive eight-figure General Fund deficits forced layoffs, pay cuts and hiring freezes. All other spending — on hiring cops, paving roads and opening libraries — got crowded out to pay for pensions.

Why did we lose so many officers before the passage of pension reform? For the same reason why I — and almost 70% of San José voters — supported pension reform: the City ran out of money. Annual costs for retirement benefits — spurred by a $3 billion debt in those pension accounts — skyrocketed; by 2013, the City was paying $200 million more for annual retirement benefits than the decade before. Consecutive eight-figure General Fund deficits forced layoffs, pay cuts and hiring freezes. All other spending — on hiring cops, paving roads and opening libraries — got crowded out to pay for pensions.

Remarkably, we didn’t reduce spending on police budgets. Indeed, over the decade prior to 2012, San José spent 47% more on our police department than the decade before, but spiraling costs for benefits like pensions forced us to employ fewer people.

So it’s critical to reform these cost structures. With some changes in place, and with mildly recovering revenues, we have an opportunity to restore police staffing. For that reason, in August of 2013, I crafted a plan with Mayor Chuck Reed to restore our thin policing staff by adding 200 street-ready officers within four years, a 20% increase in patrol staff. The Council approved the proposal by a 10-1 vote in September of 2013.

The cost of that proposal could reach $50 million. Within the proposal, Mayor Reed and I identified about $35 million in funding sources for the new hires. We will need to find additional savings or revenues over the next four years to cover the rest.

The cost of that proposal could reach $50 million. Within the proposal, Mayor Reed and I identified about $35 million in funding sources for the new hires. We will need to find additional savings or revenues over the next four years to cover the rest.

In October, we implemented the first element of that strategy, by agreeing to restore officer pay 11% by the end of 2015. We also voted for an additional one-time retention incentive, as Councilmember Pete Constant and I proposed months before.

Critically, we did all of that without returning to failed policies of the past. Those failed approaches — promising unsustainable pensions, retiree medical benefits, sick-leave payouts, or other costly benefits — might or might not stem the tide of officers leaving San José for higher-paying cities, but they’d undoubtedly put the City on a path to bankruptcy.

OFFICER RETENTION

Three police academy classes have graduated since we resumed hiring last year, adding dozens of officers. That’s not the end of the story, unfortunately: with officers departing the department for higher-paying jobs in other cities, we have to work to retain them. Fortunately, the 11% pay restoration approved in December of 2013 appears to have reduced the bleeding of new recruits after graduation — at least for now.

Nonetheless, media accounts of freshly-badged officers departing for higher-paying departments have stuck in the craw of many tax-paying San José residents. Given the roughly $170,000 cost of recruiting, educating and training an officer in San José, we would all rather not see our tax dollars used to send San José’s finest patrolling the streets of Los Gatos or Palo Alto.

Recently, I’ve proposed an alternative: a loan. That is, I proposed that we require an aspiring recruit to sign a contract before she enters the Police Academy, clearly requiring that if the officer does not serve say, five years in San José, then she (or more likely, her hiring city’s police department) would swallow a percentage of the training costs.1 While the attorneys determine whether we can move forward with such an approach absent union agreement, I will insist that a similar measure be included in the next contract we sign with the police union.

That being said, there remain areas of common agreement with the police union where we could improve retention. The rank-and-file’s misgivings about changes in disability protections for officers injured in the line of duty have severely undermined morale. Clarification of those changes through the Municipal Code — to ensure that officers know that a career-ending bullet wound would not deprive them of their ability to provide for their family in another role in the Department — would help greatly. We can find common ground with our officers to improve retention, both by clarifying disability protections, and in restoring pay at a rate we can afford.

WHAT DO WE DO IN THE MEANTIME?

Now, if we just hire officers faster, and retain our existing officers we should “solve” our crime problem. Right? Not quite. The conventional wisdom, particularly as described by the media, will urge us to believe so. If we just hire more cops, and do so faster, we’ll see much less crime.

There are two problems with this line of thinking. First, there are natural constraints to the rate at which we can hire more police — the budget being only one (though a very big one) of those constraints. San José’s police academy’s capacity, the number of field training officers on duty, and other limited resources constrain the rate of new hires, to about 130 per year. There also exists a limited supply of the highly qualified candidates that meet San José’s rigorous standards for hire. The Department is hiring as fast as it can.

Given the number of current officers approaching retirement age, we know it will take several years before we can confidently predict getting another 200 officers on the street.

So, a more important question for an aspiring mayor is, “What will you do in the meantime?”

MORE POLICE OFFICERS HELP, BUT ARE NO PANACEA

The second flaw afflicts the conventional wisdom surrounding crime: more officers may not “fix” our crime problem. In other words, if we do little more than merely add officers, we won’t likely see substantial reductions in crime. Why not? Our experience — and most studies — show a surprisingly uncertain relationship between crime rates and police staffing.2 Many cities with higher police-per-resident ratios have far higher rates of crime than San José’s, and many Bay Area cities have seen larger surges in property crime in recent years despite added police staffing.

San José’s own experience is instructive. The size of our police force has shrunk by more than 25% in the last half-decade. Yet the FBI and SJPD report that crime in San José — as defined by the number of major felonies, ranging from burglaries to homicides — has dropped over 19% since 2012.3 Contrary to the media hype, we have lower rates of crime today than when I came into office in 2007, far lower rates than prevailed when I graduated from high school in San José twenty years before that.

How do we explain that?

Criminologists insist that larger social and economic factors drive crime trends more than police staffing. Those factors — such as illicit drug and alcohol use patterns, age demographics, employment opportunities for young males, school drop-out rates, widening income inequality and the like — ebb and flow with little regard to police staffing.

For example, in California over the past three years, some 35,000 inmates have been released from state prison as a result of the state’s “realignment” policy, and the jury remains out about the impact of realignment. Prompted by a court order to reduce overcrowded prisons, tens of thousands of felons have now become the responsibility of cities. Those cities lack any new resources to prepare for the infusion of thousands felons into their communities, despite the best efforts of counties that do.

Numerous other factors play a role. Cuts in state and county mental health and addiction treatment services leave San José with more untreated, unstable individuals on the streets. Rapidly rising rents have also pushed many people on to the streets, where they face increasingly desperate circumstances that make them more likely victims or culprits. Some even blame technological change; one San Francisco account attributed the 22% increase in property crime in that city in 2013 to the increasing prevalence of easy-to-steal smartphones and tablets.4

Then, am I suggesting that we don’t need our police officers to halt crime?

No. All things being equal, more officers will help us to reduce crime. But all things are not equal. There are many changing factors in this fluid picture. More police, without better strategy, won’t alone solve the problem.

So, a safer San José requires far more than reciting the tired maxim that “we need more cops.” We also have to do things differently — and spend our scarce resources more efficiently. Restoring public safety within our means requires, simply, innovative thinking.

2. Leveraging “Force Multiplying” Technology and Approaches to Support Our Officers

DATA ANALYTICS

In the Spring 2013 budget process, at the peak of public concern about crime, some of my colleagues urged that we purge every fund possible to hire more police officers. We allocated more funding for cops, a decision that I supported. But I also publicly advocated for modest funding to create an additional crime analyst position.

Why an analyst? What will somebody behind a desk with a computer do to help us combat crime?

We all agree on the need to hire more officers. But a police officer costs taxpayers $190,000, and for half as much money, we could hire a data analyst to implement a tool that could make our existing force of over 900 officers far more effective.

How? Through predictive policing. Using the same data analytics tools as many of our Silicon Valley companies, we can process and interpret large quantities of data to anticipate where crime “hot spots” will likely emerge.

“Hot Spot” policing — concentrating police patrols at “problem blocks” within a city — has long shown to be effective as a means of reducing aggregate crime.5 The strategy relies on an intuition born out by experience: criminals tend to focus their work within relatively small geographic areas, a couple of blocks at a time.

This begs the question: how do we effectively identify those “Hot Spots?” Many cities’ police departments implement a simple “cops on dots” approach: dots on a map indicate where a crime has been reported, and officers are deployed to focus on the “dots.” Borrowing from then-New York City Chief William Bratton’s successful approach with “CompStat” in the 1990s, many police chiefs — including San José’s — have successfully reduced crime through “hot spot” policing using this simple tool.

Yet crime migrates geographically. Burglars don’t hit the same houses, or the same blocks, in successive weeks. Identifying where crime is now won’t necessarily do much to tell us where the crime is most likely to occur in the future.

In recent years, companies like PredPol have used data analytics and sophisticated algorithms to help police anticipate those movements in criminal activity for property crimes like burglaries and auto theft. By doing so, their software can provide a “force multiplier” for a very thinly staffed department, like San José’s. In Los Angeles’ Foothill Division, the department employed predictive policing software to reduce crime 13% in four months, while the rest of the city experienced a 0.4% increase in crime. Other cities, like San Francisco and Sacramento, have increasingly taken on PredPol as well, with positive results.

I have urged San José to take the lead in employing this innovative approach. My proposal for an analyst position to support that Safer City, Smarter Government by Sam Liccardo 17 transition was not incorporated in the 2013 city budget, but the police have moved forward to explore a pilot project with PredPol software. More can be done. The department will need civilian support staff capable of processing and interpreting data to make predictive policing work, and ensuring that officers have actionable and readily available information. While we have many needs in our understaffed police department, we should start by funding those lower-cost initiatives that can provide a “force multiplier” for our existing officers.

OFFICER-MOUNTED CAMERAS

Technology can help our short-staffed police in other ways as well. Video camera technology has evolved to the point where any officer can wear a micro-device on her or his uniform, without interference or nuisance, and adequately record whatever transpires in the officer’s presence. Though far from exotic, this technology can save thousands of police officer hours annually, along with millions of dollars from thin Department budgets.

Here’s why: our officers spend thousands of hours each year sitting in court, waiting their turn to testify in routine hearings in which criminal defendants and their attorneys challenge the lawfulness of an officer’s seizure of evidence, or of an arrest, or of an interrogation. Those hearings routinely result in a judge’s finding that nothing improper occurred. Nonetheless, every defendant has a right to such a hearing under the Fourteenth Amendment; with nothing to lose, many defense attorneys will “roll the dice” to see if something untoward turns up during their cross-examination of the officer. When the hearing concludes, and a judge renders her finding, defendants often plead guilty.

Our city also spends millions of dollars each year defending — and paying out settlements for — civil rights lawsuits filed by individuals alleging maltreatment or police misconduct of some kind. When their claims are substantiated, wrongdoing is exposed, plaintiffs are compensated and officers are disciplined. Cameras would hasten those findings: the “bad apples” would be exposed unequivocally, and good officers would not have their reputations sullied by false accusations.

Much more often, hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars are expended in largely frivolous claims. Settlements are paid out by frustrated city councils that can more cheaply pay, say, $50,000 to “make the case go away” than to spend $200,000 in attorney time battling in court. These “nuisance settlements” add up. Nationally, cities spent some $2.2 billion on legal settlements and jury awards alone — not counting the millions of hours of lost officer and attorney time.

In every case, consider the millions of dollars that could be saved if factual disputes about “what really happened” were immediately resolved with a videotape record. Consider the extraordinarily painful experience of Ferguson, where accusations fly about an officer’s motives for shooting an unarmed African American college student. A video recording could help resolve unanswered questions.

As Independent Police Auditor LaDoris Cordell has long advocated, I proposed in early 2012 that the City avail itself of federal grant funding to acquire officer-mounted micro-cameras, which would videotape routine events during the officers’ shifts. Although we did not obtain funding in that grant cycle, more recently, several colleagues joined in to call for implementation of body-worn cameras.6 The Police Department has now begun serious evaluation of the implementation of this technology. We need to get this initiative over the goal line, because a relatively small investment in this technology could pay huge dividends, particularly by freeing our time-strapped officers to spend more time in our neighborhoods than in court.

“CROWD-SOURCING” PRIVATE VIDEO SURVEILLANCE

Residents glued to their nightly news stations during the serial arson attacks east of Downtown will attest to the power of privately-generated video footage in identifying the suspect. Residents near targeted homes captured the arson suspect pacing before and after the arsons, enabling police to corroborate sketch artist descriptions of the suspect and identify patterns of behavior helpful to his ultimate arrest.

With the spate of burglaries and auto thefts, many more residents are purchasing video security systems for their homes, and in any given neighborhood, dozens of such systems proliferate. Many of us are uncomfortable with the idea of “big brother” watching our every move, but nobody objects to the idea of police asking residents to provide video footage when a crime has occurred nearby.

An opportunity exists here to leverage these collective efforts. Some cities are asking residents, shop owners and other property owners to voluntarily register their video cameras,7 and to indicate areas that are covered by them. In Philadelphia, police have used their “SafeCam” program to provide evidence leading to 200 arrests. Residents can readily do so online,8 and little city staff time is required to maintain a simple database. We can also strike deals with security system installers to engage in group discounts of such video systems where residents choose to register their system.

This simple use of familiar technology can save investigators hours of painstaking effort to find residents with video footage. Most importantly, where many of these systems will only store video records for a few days, we can ensure the preservation of often-crucial video evidence. The Council passed my proposal this September to create a voluntary surveillance camera registry in San José.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND GANG CRIME

Finally, even social media can assist crime-fighting. Chicago’s anti-gang efforts have relied on Facebook and Twitter to identify and map the social networks of perpetrators and victims of gang violence,9 and to proactively make contact with those individuals after gang violence has occurred. Why? We know that gang crime breeds more gang crime, in the form of retribution against a rival gang for a killing, or by those gang members who “claim turf” in response to recent intrusion to their neighborhood. Friends and associates of gang violence victims have an extremely high propensity to become involved in subsequent violence, as victims or as perpetrators. By leveraging technology to better anticipate — and prevent — violence, we can better deploy our scarce officers where they will have the most impact.

CIVILIANIZATION

As we face challenges in hiring officers quickly enough to restore our depleted department, we need to leverage the work of civilians to ensure that officer time will be focused where it will have the biggest impact. Currently, the Police Department has several dozen vacant positions in the sworn positions, and the Chief has budgetary authorization to hire a far larger number of officers than he can possibly screen, hire, train, and deploy.

Given the less stringent requirements, less extensive training and lower cost of non-sworn personnel, it makes sense for us to focus on hiring whoever we can to help take on the less critical tasks of the Department. For example, for years in my tenure at the DA’s office, I was repeatedly surprised by the frequency with which sergeants and other detectives in an Investigations Unit would answer incoming calls and play “receptionist” for other investigators. Obviously, the time dealing with calls and taking messages from prosecutors, members of the public or others detracts that same detective from investigating a case. When I asked about this problem years ago, the response was typically, “budgets are tight, so we had to let go of the civilians.”

On the contrary, when budgets are tight — and particularly where we cannot hire officers fast enough to fill the obvious need — we should be hiring civilians wherever we can to substantially improve the efficiency and effectiveness of our sworn patrol officers.

In 2013, with a depleted patrol staff unable to respond to burglaries and other nonviolent crimes in a timely manner, the Chief experimented with the hiring of twenty-nine “community service officers” (CSOs). CSOs will perform the tasks that our overburdened officers lack the time to complete, such as taking witness statements, lifting fingerprints at the scene of a burglary, or tagging and transporting evidence to storage. After training and classes, the first class of CSOs are hitting San José streets this Fall.

In 2013, with a depleted patrol staff unable to respond to burglaries and other nonviolent crimes in a timely manner, the Chief experimented with the hiring of twenty-nine “community service officers” (CSOs). CSOs will perform the tasks that our overburdened officers lack the time to complete, such as taking witness statements, lifting fingerprints at the scene of a burglary, or tagging and transporting evidence to storage. After training and classes, the first class of CSOs are hitting San José streets this Fall.

While many Bay Area cities share our challenge in identifying and recruiting highly qualified officers to live in our high-cost area, we can hire more CSOs at a far lower cost to help focus sworn police on their most demanding tasks. We can also create a ready pool of potential recruits for our ranks of police officers, a police “farm league” of CSO’s who will have gained experience working within the Department. The City should expand the CSO program, enabling existing officers to spend more of their scarce time investigating, deterring and responding to crime. Other opportunities for civilianization exist, and I’m willing to explore any of them that help keep us safer without spending more.

3. Addressing Gang Violence: Investigations, Injunctions and Youth Jobs

Gang violence has long been a scourge in every major U.S. city, and San José is no exception. San José has long touted what has become a national model for engaging non-profit organizations, the faith community, schools and the police in gang-prevention and intervention with youth. Known formally as the Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force, it provides a good approach from which we can build our gang-prevention efforts.

In recent years, to address the shortfalls of police staffing, Chief Larry Esquivel has refocused resources on gang abatement and patrol, and the Mayor and Council have boosted funding commitment to programs overseen by the Gang Prevention Task Force. We’ve seen gang crime drop considerably in the last two years and the rate of violent crime in 2013 reached the second lowest in a decade.

Nonetheless, we know many neighborhoods remain burdened by very high levels of gang-related crime. We can do better.

As Mayor, I’d drive a comprehensive approach consisting of five key elements: extending gang detective tours in investigations, renewing our implementation of gang injunctions, prioritizing violent crimes unit re-staffing, partnering with school districts to enforce truancy and creating more youth jobs. Here’s how I’d do it:

First, we have traditionally rotated detectives in and out of our Gang Unit every three years. Just as detectives have begun to develop expertise, strong contacts in the community and awareness of the complex interrelationships of San José’s many gangs, they move on to patrol or another job. This loss of institutional memory comes at a steep cost. We should lengthen the duration of an officer’s tour of duty in the Gangs Unit to at least five years.

Second, it’s been more than 16 years since the City sought its last gang injunction. These tools can become particularly valuable in disrupting deeply established patterns of gang dominance in particular neighborhoods, by implementing court-imposed “stay away” orders on gang members in key areas with disputed turf or a high propensity for crime. When seeking to implement gang injunctions, however, we frequently hear from our justifiably frustrated peers in the City Attorney’s Office and SJPD that they lack the manpower to be able to implement and enforce a gang injunction effectively.

Partnerships and technology can help. The District Attorney’s office has restored funding to its “community prosecutor” program, and is evaluating adding several more positions to that office. We could engage with DA Jeff Rosen to identify a single community prosecutor focused on establishing and enforcing gang injunctions. Leveraging video camera and storage technology that has become more affordable and ubiquitous, we can employ non-sworn staff to help monitor compliance in gang-intensive neighborhoods remotely, and SJPD can enforce where violations are identified on video, by witnesses or by the police themselves.

Third, as we restore personnel in our Police Department, we must prioritize the reformulation of the Violent Crimes Enforcement Unit (VCET), or its functional equivalent — such as by bolstering the Gang Suppression team. Staffing shortfalls have forced the redistribution of VCET tasks to officers in other units (such as MERGE and Gangs). This has diluted the ability of officers to focus on suppressing violent crime and arresting the most threatening suspects. Re-instituting the focus of a separate VCET unit, or at least bolstering the number of officers in Gang Suppression, can have a meaningful impact.

Fourth, we know of a strong link between truancy and crimes like burglary, theft and gang-related crime. In Minneapolis, daytime crime dropped 68% after police began to aggressively cite truant students.10

Years ago, San José launched a very active Truancy Abatement and Burglary Suppression (TABS) program, but police staffing cuts eliminated that program. Recently, incoming Chief Larry Esquivel revived it with a small allocation of staff, a fact for which I am grateful, but his department lacks the resources to expand it to an effective size.

Fortunately, we know that our school districts benefit from a funding formula that relies on “average daily attendance,” or ADA. When we effectively deter kids from cutting school, districts earn more ADA funding from the state. There ought to be room for a stronger partnership between school districts in the city, to share resources to support truancy abatement, where both entities benefit financially and in desired outcomes.

Finally, a renewed focus on job-creation for at-risk teens could go a long way to reducing gang participation. With a recovering economy, we see new opportunities for engaging young people in the workforce. For many of our young men and women who lack the social networks, access or information to those opportunities, however, it won’t happen without a focused effort.

In August of this year, I proposed the formation of a “Water Conservation Corps” to help us confront our severe drought. The Santa Clara Valley Water District recently approved funding for 24 the hiring of staff to explore conservation efforts, and the City and other water retailers utilize outreach funding to educate users about conservation. These agencies could collaborate with such organizations as the Conservation Corps, Year Up or Teen Force to hire a group of young men and women to form a cadre dedicated to reducing water consumption citywide. Teens and young adults could be hired to drop informational literature on the front porches of homeowners identified as heavy water consumers. They could track neighbors’ complaints of water waste. They could even generate revenues for the managing non-profit organization by serving homeowners who want to reduce water bills by building grey-water cisterns or replacing lawns with drought-tolerant plants.

Without touching General Fund dollars needed for basic services like police, roads and libraries, we can leverage other sources of funding to boost summer and after-school jobs for youth. Where properly supervised by experienced professionals, for example, some young adults could gain valuable skills in the construction trades and engage in a citywide effort to replace and rebuild worn-out playground equipment, install trail and park signage, and (after the drought subsides) new turf in our parks and community centers. We have over $50 million in developer fees currently sitting in the City’s fund for park development and improvement. A very small fraction can be put to use restoring our neighborhood parks and give many at-risk youth a much-needed first step in the working world.

We can also employ new models for engaging our youth in the workforce. I’m particularly proud of Cristo Rey San José, an innovative college preparatory on the East Side, primarily focused on educating teens from very low-income, mostly immigrant families. Over the last two years, I’ve worked with several private sector and community leaders who cofounded the school, modeled on the successful Cristo Rey in Chicago, and they just opened their doors to their first class this fall. Youth obtain a college prep education by attending class as many as five days a week, but also work one day a week at the office of a local tech company, bank, hospital, or other employer. As I pitched local employers on the idea, many stepped up knowing that their “salary” to the student would pay for the majority of the student’s tuition. Cristo Rey schools in Los Angeles and Chicago have propelled 100% of their graduates to college — all of them the first in their families to do so, and all of them students who started high school a year or more behind academically. Best of all, young teens with no familial or social networks in the professional world obtain training, skills, references and resume-building that will enable their integration into the economic mainstream with their first job — a critical springboard for life.

4. Restoring Community Policing

In the 1970s, many big-city police departments devoted resources to beefing up investigation units, and to improving response times to calls for service. Building new substations, buying speedier patrol cars, and shinier crime labs, seemed a reasonable response to oft-heard complaints from residents about slow responses or unsolved cases.

The problem with all of this investment: it didn’t do much to prevent crime.

The problem with all of this investment: it didn’t do much to prevent crime.

That shouldn’t surprise us. Even if officers could instantly tele-transport themselves to crime scenes upon a call from a resident, only a very small fraction of crimes would actually be interrupted by an arriving officer. Rather, police responses to 911 calls are overwhelmingly reactive; a victim or witness has made a call after-the-fact, and the assailant and burglar has already left the scene. Contrary to popular belief, even the best police departments won’t reduce crime by simply responding faster to calls.

In the 1980s, in a now-famous article, “Broken Windows,” criminologists George Kelling and James Q. Wilson proposed a different approach to policing.11 Kelling and Wilson argued that effective deterrence requires a focus on “community policing,” whereby beat officers become proactive problem-solvers. They develop relationships within a community. They get out of their patrol cars, walk the streets, visit the schools and establish a “felt presence” in the community. They engage with residents, business owners, teachers and other key stakeholders to proactively identify ways to prevent crime.

In the words of Kelling and Wilson, they work within a community to ensure that a landord fixes the broken window in her vacant storefront. Otherwise, the window’s shattered glass will signal to the city’s rock-throwing vandals that disorder will be tolerated in that neighborhood. Within a few days, all of the windows in the neighborhood will become their targets — unless the community and police work proactively together.

So it goes with a community’s — and a police department’s — response to a streetlight outage, a drunk urinating in the park or a liquor store owner who sells cigarettes to teenagers. Where community members work together with the police to address these warning signs before they become a “tipping point” into more predatory crime, a neighborhood can prevent crime.

Along with Kansas City and New York, San José pioneered community policing in the 1980’s — with excellent results. Today, efforts to implement community policing continue to bear borne fruit; even crime-ridden Detroit recently announced an effort that reduced home invasion burglaries and robberies by 26% in one year.12

Community policing requires many elements, but above all, it requires a relationship between a patrol officer and a community. San José’s policy — long-enshrined in our contracts with the police union — has officers rotating out of neighborhoods as frequently as every 6 months. Just as they’re getting to know a neighborhood, and its residents — and perhaps more importantly, just as some residents have begun to Safer City, Smarter Government by Sam Liccardo 27 develop relationships with those officers — the officers move on. The trust and spirit of collaboration that develops between officers and a community takes time to develop. Six months is simply too short.

Neighborhood leaders have long urged that they want to build better relationships with the police, and they point to the 6-month shift change as a primary culprit. Their intuitions appear well-founded in fact: in the words of one expert, experienced officers can recognize the people and places of a familiar neighborhood “in such a way that they can recognize at a glance whether what is going on within them is within the range of normalcy.”13 An experienced officer immediately notices the reputed gang recruiter in the grey truck who hovers near the school, and she knows the taqueria owner who can quietly provide reliable information about nearby drug dealing.

Mark Twain famously warned that “Familiarity breeds contempt — and children.” Yet familiarity also breeds better policing. Local residents and other stakeholders may not share information with officers they do not know and trust. Officers lacking familiarity with a neighborhood will not recognize phenomena — a group of unfamiliar teens hanging out in the park, or example — out of the “range of normalcy” in the local streetscape. To restore relationships between police and the community, we need officers familiar with their communities. We need to extend those 6-month shift durations.

Other measures can help improve police-community interaction as well, and they don’t cost a lot. With severe cuts in mental health treatment at the state and county level, our officers encounter many more people with mental illness on the street. Ensuring that the police have the proper training — known as “crisis intervention training” or “CIT” — will be critical. Although the SJPD began offering CIT training in the Academy in 2009, only a fraction of more senior officers have taken a CIT course, and it’s currently voluntary. In other cities, like San Francisco, CIT training is mandatory. We need to train every patrol officer to deal with the very unpredictable challenges posed by mental illness, particularly where appropriate interventions can avoid the escalation that can result in violent harm.

We also need to improve communication with non-English speakers in our community. Almost forty percent of San José’s adult residents came here from a foreign country. Our increasingly diverse city remains one where many languages are spoken — and we need officers capable of communicating with our residents, particularly during natural disasters and crises.

In some apartment buildings and whole neighborhoods in my Downtown district, the majority of residents will consist of monolingual Mandarin, Spanish, or Vietnamese speakers. Only a minority of our police force, however, has fluency in a foreign language. This has long been the case; as a criminal prosecutor a decade ago, we faced a critical shortage in the number of investigating officers fluent in Spanish and Vietnamese to communicate with victims and key witnesses. Although prosecutors typically shouldn’t talk with witnesses for evidentiary reasons, our shortage often required me to follow-up (with my then-barely-adequate Spanish) with Spanishspeaking victims and their families.

Months ago, the Council approved a substantial boost in bonuses for bilingual officers, without asking the police union for any concessions. That offer awaits union approval.

We can pay more, but we should also expect more. Every incoming officer who lacks a second-language skill should be taking classes in Spanish, Vietnamese or another critical language — at City expense. Victims, witnesses, and residents cannot trust someone with whom they cannot communicate, no matter how sincerely the officer seeks to help them.

By improving the relationship in each patrol officer’s encounter with every community member, we can do much to improve policing itself. With that, we can all feel safer.

5. “Bowling Together”: Helping Communities Take Back Their Streets By Building Social Capital

One morning in 2010, a group of Spanish-speaking parents at Washington Elementary School — almost entirely women — invited me to a cafecito in the school library. Maria Villalobos, and her husband, Juan, each spoke up, expressing frustration at the looming presence of pandillas — gangs — around the school in the afternoons, menacing the children and instilling fear throughout the neighborhood. Other members of the madres joined in, and shared their fears.

One morning in 2010, a group of Spanish-speaking parents at Washington Elementary School — almost entirely women — invited me to a cafecito in the school library. Maria Villalobos, and her husband, Juan, each spoke up, expressing frustration at the looming presence of pandillas — gangs — around the school in the afternoons, menacing the children and instilling fear throughout the neighborhood. Other members of the madres joined in, and shared their fears.

Crime has long afflicted the Washington Guadalupe area of my district. I suspect it was so from the time that my grandmother lived there (when it was known as “Goosetown,” populated by Italian immigrants) in the early part of the last century. Yet through this period in 2011, we suffered dramatic reductions in police ranks — we had just laid off 66 officers due to budget cuts, and diminished resources inhibited the City’s ability to respond meaningfully.

I discussed the problem at length with Ruth Cueto, a bright Cal Berkeley grad who serves on our council staff with responsibility for the Washington neighborhood. We reached out to the local police captain, to residents and to school principal Maria Evans, who had long hosted the madres in weekly gatherings.

Ultimately, we encouraged the parents to take action on their own: to form a walking group that would accompany children on their way home from school. The parents agreed, and called themselves “Washington Camina Contigo.” (“Washington Walks With You”). While they’d walk, they’d carry a notepad and a cell phone, and they’d identify graffiti, street light outages and other issues that could be reported to City Hall. Ruth worked to organize the parents into walking groups. Maria Evans chipped in for bright vests, whistles and clipboards.

Soon, a dozen parents started a walking routine in the morning, and again in the afternoon after school. Their numbers grew. Parents got to know one another, and communicated with each other. They reported problem behaviors to school officials and the police, and notified Ruth of any physical conditions needing improvement in the streetscape.

Did crime magically disappear from the neighborhood? No. But fear diminished greatly. Parents recognized that by bringing more “eyes on the street,” they could discourage gang members and recruiters from hanging around the school. They recognized the power of numbers — their numbers — and that gang members thrived in environments where people shunned going outside, or talking to one another. Now, a graffiti-tagging 14-year-old wasn’t simply “the problem”; he was the son of fellow parent who could be approached and admonished. And yes, to most observers, the effort did appear anecdotally to diminish crime and gang activity near the school. With the success of Washington Camino Contigo parents received awards from the City and the County for their successful initiative.14

In many neighborhoods, the most important thing that City Hall can do to improve safety lies in convening residents and other stakeholders to work together.

Residents in highly-engaged communities don’t merely sigh when they see the 14-year-old tagging the wall near the freeway, or taunting another kid in the park; they call his parents. If their neighbors forget to halt newspaper delivery while on vacation, they collect the paper from the driveway to avoid attracting burglars. They call the City when cars appear to be abandoned on their street, they host block-parties to encourage neighbors to get to know one another, and they check in on elderly neighbors during a heat wave in August.

Take a more dramatic example: when a serial arsonist terrorized several Downtown neighborhoods in January of 2014, the community reeled from the succession of 13 fires of homes, churches and businesses over four nights. Working with the police and fire departments, I launched an effort with dozens of committed neighbors to establish “block watches,” to provide fire alarms and batteries to local residents, and to distribute police sketches of the suspect to over 3500 homes. Residents provided police with video footage and tips, leading to a multi-day surveillance of the suspect’s home, and his ultimate arrest. All of these actions make for a safer neighborhood. Most of them don’t cost the City a dime.

Robert Putnam, author of the seminal work, “Bowling Alone,”15 referred to the phenomenon that exists in engaged communities as “social capital.” Residents in neighborhoods with high levels of social capital become heavily involved in civic, social and religious organizations — characterized by participation in Little League or Rotary, or by regular attendance at the synagogue, PTA meetings or neighborhood association gatherings — in ways that establish strong networks of relationships. Even in very diverse communities, they share fundamental norms of behavior, such as the propriety of scolding another parent’s 14-year-old when unsightly teenage behavior rears its head. They develop bonds of trust.

Studies throughout the world have demonstrated that communities with high levels of social capital see reduced crime.16 They also see a host of other benefits — greater levels of self-described satisfaction, reduced rates of suicide, higher levels of economic activity, and even lower rates of heart disease.17

How does San José fare in building social capital? Studies appear mixed. Over a decade ago, a Mercury News headline famously called Silicon Valley the “Valley of Non-Joiners,” describing a study reporting 32 our low levels of volunteerism, participation in social and community organizations, and charitable giving relative to other regions nationally. More recently, a 2012 community survey revealed that fewer than a quarter of San José residents volunteered in the prior year, and about 12% participate in a club or civic group. Slightly more than half of San José residents reported having talked to or visited with their neighbors a few times a month. Finally, the Knight Foundation’s “Soul of the Community” study gave San José high scores for social capital in 2010 and 2011.18

Rather than debating which view better approximates the truth, we’d better spend our time exploring ways that we can build social capital that makes our communities safer.

How can City Hall help build greater social capital in San José?

START BY GETTING OUT OF THE WAY: REDUCE FEES FOR NEIGHBORHOOD GROUPS

Neighborhood groups, nonprofit community associations, and civic clubs of all types would love to use San José parks and community centers, and other facilities to convene people. These grassroots gatherings are often the lifeblood of our community, bringing diverse people together socially, enabling them to meet one another, to build trust and relationships critical to tackling the challenges in their own communities.

Typically, we charge hundreds and even thousands of dollars for the use of these facilities, at rates that are frequently prohibitively high for organizations that serve working-class families. On the other hand, the revenues we generate from park and facility rental are relatively low; at a typical community center, the City generates no more than a few hundred dollars from local neighborhood associations.

Typically, we charge hundreds and even thousands of dollars for the use of these facilities, at rates that are frequently prohibitively high for organizations that serve working-class families. On the other hand, the revenues we generate from park and facility rental are relatively low; at a typical community center, the City generates no more than a few hundred dollars from local neighborhood associations.

Simply, we should reduce fees for park or community center use by designated neighborhood associations and community-serving non-profits to something minimal, such as $50. Any foregone revenue will be very small, particularly when we consider the extensive investments that the city already makes through grants and programs for ostensible “community-building.” By getting out of the way of organic, neighborhood-led community-building, we’ll do far more to support our communities.

ON-LINE TOOLS

Nextdoor has developed an on-line platform for neighborhood residents to communicate with one another exclusively (explore for yourself at www.nextdoor.com). Many San José neighborhoods have taken advantage of this tool to, for example, ask for help with a lost dog, warn their neighbors of recent bike thefts or burglaries, or even to band together to purchase cameras to monitor problem streets. The city has only begun to develop means to take advantage of this resource, with some occasional announcements from the police or the Office of Emergency Services, but we can do much more. We can disseminate the latest information on arrests and crimes in that neighborhood. We can solicit residents to come forward with any information about particular crimes or vehicle accidents they may have witnessed. By having City Hall participate more directly in on-line tools like in Nextdoor, we can encourage greater participation from the entire community, and make that engagement meaningful in reducing crime.

6. Regionalize Crime-Fighting

Criminals don’t respect much, and they certainly don’t respect municipal boundaries. Thieves steal cars in Palo Alto, take them to 34 chop shops in Fremont and fence the parts in San José. Whose police department should investigate the crimes? For years, cities in Santa Clara County have relied upon a regional auto theft task force to deal with the multi-jurisdictional nature of auto theft.

Similarly, we frequently see crimes like burglaries committed by small groups of persistent criminals. Expanding regional task forces to include burglary investigations provides a win-win; San José lacks the manpower to devote to a sizeable investigation team for property crimes, and neighboring cities like Campbell recognize that the largest percentage of burglary culprits hail from San José.

Prostitution has become another sore spot for many residents living near Monterrey Road, North First Street, or even the Alameda, and we’ve seen a large influx of prostitutes and pimps from the Central Valley and East Bay. Taking a regional approach could do much to ensure that we’re quickly arresting pimps on probation in other counties, sharing information, and sending them back to their home county jails.

None of us want to hear that we need to ask for help. We do. In the downtown, we started meetings in 2012 with multiple agencies to address the crime problem there, and several partners have stepped forward in response. I reached out to then-VTA General Manager Michael Burns to increase the VTA’s budget for deployment of additional sheriffs’ deputies to patrol the transit mall, and to use federal grant funds for deployment of video cameras in that area. District Attorney Jeff Rosen restored the community prosecution office, which targeted owners unwilling to curb drug, gang, and prostitution activity on their properties Downtown. The San José Downtown Association elicited funding from its member property owners to pay for additional police security. We’ll need all these efforts and more — particularly from our community partners in education, gang prevention and domestic violence — to make real progress.

7. Gambling, Booze and Weed: Common-Sense Approaches to Businesses That Impact Our Quality of Life

Many residents throughout central San José and the East Side know well that some businesses — such as liquor stores, card clubs, bail bonds dealers, strip clubs and marijuana dispensaries — can have uniquely negative impacts on surrounding neighborhoods. Many of these establishments are well-managed, law-abiding and owned by upstanding local businesspeople. Their good intentions don’t change the substantial impacts of their business’ operations, however, and those effects are felt most acutely in neighborhoods that struggle the most with crime.

During a time when our police force appears so thinly staffed, we could go a long way to support their crime-fighting efforts by standing up to industries that have criminogenic impacts on our community. These businesses typically have owners with significant political sway, often through contributions to campaigns, or more ominously, through independent expenditures to political parties and political action committees. In the primary election of this mayoral race, for example, card clubs contributed $50,000 to an “independent” committee supporting Dave Cortese — and that was just for starters. In a time with highly constrained police resources, San José needs independent leadership capable of standing up to well-financed businesses like these, and applying common-sense regulations to their operations.

Those regulatory tools will differ in each case. When motels frequented by a high volume of prostitution on South First Street seemed to do little to address the impacts of the johns and pimps on nearby residents and businesses, I urged our City Attorney to get involved. We took on the motels that profited from prostitution, threatening nuisance suits against those that continued to take cash for short-term room rentals. We shut down one operator, the Hotel Elan, with a nuisance suit.19 (Community engagement played an important role, as the nearby Washington Guadalupe neighborhoods joined in with protests). We can expand nuisance suits like these with 36 the help of a willing District Attorney, who has already taken steps to beef up its community prosecutions unit for such purposes.

In other instances, a sensible approach to regulation calls for a more nuanced approach. When I ran for my council seat in District Three, I heard endless complaints about the drunks, drug dealing, loitering and underage activity near some corner grocery stores that predominantly sold alcohol along with junk food and cigarettes. I pushed against the issuance of new liquor permits for small markets in oversaturated neighborhoods. We worked with owners to convert two of the shops into more neighborhood-friendly uses: a child-care facility and a gym. Additional help is coming with the Health Trust’s recent launch of its “Healthy Corner Store” initiative, to provide incentives for owners to sell more fresh food and less booze, and we can support those transitions by spreading a good word about those community-minded storeowners.

The City can go a step farther, offering to liberally “up-zone” liquor store sites, to incentivize property owners to redevelop the properties for community-serving retail and residential uses, and to waive the City’s fees for doing so. Converting a liquor store into a three-story apartment building over a bagel shop or café brings extraordinary benefits to surrounding neighbors and property owners, and the new tax revenue will more than compensate City coffers for any waived fees.

Motels and liquor stores provide just two examples of lawful, legitimate businesses that can have criminogenic impacts in a neighborhood. Two other businesses seem to get the lion’s share of media attention, however: card clubs and marijuana dispensaries.

CARD CLUBS

Gambling has had a long history in San José, and we’re only a generation removed from the day when criminal indictments against local card club owners made the headlines. Fortunately, today San José has more reputable ownership with regard to one of its two card clubs, Bay 101. The other club, on the other hand — Casino M8trix — recently made headlines when the California Attorney General charged the casino for skimming over $70 million from City and State regulators and tax collectors.

The real problems, though, arise from gaming’s broader impacts in the community, often far removed geographically from the clubs themselves. Several studies point to the increase in crimes — such as burglary, loansharking, robbery, child neglect and even domestic violence — resulting from the introduction or growth of casino gaming in a community. One peer-reviewed study published in the Review of Economics and Statistics assessed crime rates before and after the introduction of casinos in U.S. communities between 1977 and 1996. Using a technique called regression analysis, authors Earl Grinols and David Mustard found that an average 12.6% of a county’s violent crime, and 8.6% of its theft and property crime could be attributed to the presence of a casino nearby.20 In other words, although gambling aficionados can always avail themselves of internet gaming, something uniquely impactful emerges from the brick-andmortar presence of a card club in a city.

Card clubs have made two efforts to lift the limits of the San José charter to expand gaming operations with ballot measures in the last halfdecade; one succeeded in 2010, and the other, in 2012, failed. I opposed both ballot measures, for a simple reason: our police have enough to worry about already with the clubs’ activity. In the 2012 campaign, after one club spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to weaken casino size restrictions and police oversight, I wrote the opposing argument on the ballot, and rallied other prominent community leaders to sign on.21 Fortunately, San José voters agreed with us. Yes, even in politics, good sense can prevail over money and influence.

In January of 2014, Casino M8trix persuaded my Council colleagues to water down the City’s oversight of the clubs. For example, M8trix sought to have state regulators replace City officials in performing criminal background checks on card club employees. I vocally opposed this effort.2 San José’s other card club, Bay 101, expressed no concerns with SJPD’s employee screening processes, likely because the process wasn’t broken: the City has issued work permits to over 1,100 casino employees within 20 days of their application. Remarkably, even though 38 the State of California publicly admitted that it lacked any resources to screen casino employees — virtually assuring a lack of any meaningful background checks — the Council approved this change.

Months later, the California Attorney General filed charges against Casino M8trix, seeking revocation of its license for fraudulently skimming over $70 million in profits, defrauding taxpayers and a local nonprofit of millions. I urged that the City begin revocation proceedings of M8trix’s City-issued permit, to finally halt its operations.

My initiative was deferred by the Council’s Rules Committee, which preferred to allow the State proceedings to conclude. In the meantime — likely several years — M8trix continues to operate. San José’s next mayor must take a clear stance against allowing further growth in this industry, and against the weakening of sensible regulations over casino operations. The clubs make ample revenues at their current size, and our police don’t need to be any more occupied with calls than they already are.

MARIJUANA DISPENSARIES

The Council has repeatedly tried to tackle marijuana regulation, against the well-financed legal and political challenges of the industry. Wellmanaged dispensaries provide a drug of which genuinely ill patients properly avail themselves, as contemplated by the voter-approved Compassionate Use Act. Yet many poorly run dispensaries, however, have become the targets of scorn from nearby residents and businesses. Angry calls come to City Hall daily regarding thuggery, burglaries and robberies of cash-heavy dispensaries, secondary drug dealing in adjacent parking lots, loitering and frequent use of the drug around children.

Finally, this Spring, we mustered the votes to get a sensible regulatory package passed at Council, forcing dispensaries currently located in neighborhoods and retail centers to shut their doors and move to commercial sites distant from ready exposure to children. Some dispensaries will sue, others will fail to comply, but at the very least, we can expect some relief in many neighborhoods from their less desirable impacts.

In the longer term, as Mayor, I intend to advocate at the federal level for changes in the federal Controlled Substance Act. Those changes would allow the drug to be dispensed by medical professionals in pharmacies, and regulated by the FDA, rather than by poorly regulated, fly-by-night dispensaries that cause as many headaches for neighborhoods as they purport to solve for patients.

8. Reducing Crime By Improving the Streetscape

We can also employ familiar tools to affect the physical environment to address high-crime hotspots. Installing speakers to play classical or soft music has been shown to scatter drug dealers and loiterers from “problem corners” and lots.23 Our use of cameras at Fountain Alley and along the transit malls in Downtown San José has reduced drug dealing, though we continue to focus police presence there.

The tools with the greatest impact on a physical environment, however, are eyeballs. Creating settings where people will want to walk, eat or otherwise linger outside, “bringing eyes to the street,” can have a profound effect on the sense of safety, and on actual crime. Drug dealers and thugs prefer to engage in their activities discretely. For that reason, I’ve pushed to reduce fees and streamline the process to enable restaurants to obtain sidewalk permits, to bring patrons outside to enjoy San José’s 300 days of sunshine a year. Where sidewalks did not appear wide enough to accommodate outdoor dining, I worked with the San José Downtown Association to push for a “curb café” initiative, to take up parking spaces in front of restaurants to accommodate platform decks and tables. In early 2013, I launched an initiative to fill vacant storefronts by waiving city permit fees in long-empty parcels, and providing tools like free Wi-Fi boosters to the start-up businesses that turn on the lights. These efforts, though launched Downtown, are available to businesses citywide. I will discuss them in greater detail in another chapter, focusing on creating vibrant public spaces throughout San José.

We also know that lighting in a neighborhood can have a big impact on safety. The rash of stolen copper wire has left streetlights in many of our neighborhoods out for months. The backlog of expensive repairs 40 continues to build as the City’s depleted electrician crew remains unable to catch up.

We also know that lighting in a neighborhood can have a big impact on safety. The rash of stolen copper wire has left streetlights in many of our neighborhoods out for months. The backlog of expensive repairs 40 continues to build as the City’s depleted electrician crew remains unable to catch up.

Rather than spending millions of dollars on repairs to replacing wiring for the same inadequate yellow sulfur lights, I’m pushing an initiative to replace the lights altogether with brighter, energy-efficient LED white lights at no cost to our taxpayers. How? By partnering with the private sector. Companies like Philips have sought to pilot their “smart light pole” technologies in locations where it can also expand wireless capacity with cell base stations planted on each pole. Philips generates revenue from telecom service providers that pay rents for the usage of the cells by their customers, while our residents benefit both from the rapid upgrade in lighting and in cell phone coverage — particularly for data. The poles’ wireless capability, also instantly informs City maintenance officials when the longer-lasting LED bulbs need replacement, and can be dimmed remotely to save energy. I introduced this effort in November of 2013 with Councilmember Rose Herrera, and am currently pushing to get it implemented. It will be a top priority of mine as Mayor.

Installing better lighting in our neighborhoods at no cost to taxpayers seems compelling enough, but best of all, it can have substantial benefits in providing a safer streetscape for our residents.

With an eye to these kinds of elements, a creative City Hall can work the private sector improve the built environment to make us safer. In a world of limited resources for our police department, we can leverage developer impact fees and other sources to make our streetscapes — and all of San José — safer.

9. The Hidden Crime: Battling Domestic Violence

The wounds of domestic violence run deep in any community. Those wounds run wide, too: our County’s residents made 23,747 hotline calls to domestic violence agencies in 2012, most of them in San José. That year alone, we lost the lives of 9 victims to domestic violence.

Experts tell me that the most lethal period in the cycle of domestic violence occurs when the abused partner makes her first attempt to leave the batterer. Access to victim services, transitional housing and better coordination between police and service providers can have the most impact at that moment: in providing a flight to safety for a victim and her children.

We can do better. First, a domestic violence drop-in center should provide victims and children a safe, welcoming environment, enabling them to readily seek and find assistance, but the current center falls short in each respect. One social service provider told me that her clients can’t even find the office. District Attorney Jeff Rosen has launched an effort to create a new Family Violence center, modeled on Alameda’s promising Family Justice Center — a one-stop location for victims to seek help from medical, law enforcement, legal and social service professionals. As Mayor, I’ll be pushing to ensure City resources are committed to fully supporting a successful launch.

Second, for the critical moment when victims and their families need transitional housing, we appear severely under-prepared: in 2012, 2,504 victims could not find room at any domestic violence shelter when they needed it. Although community organizations like NextDoor Solutions admirably provide services in the face of diminishing governmental support, our underfunded local providers housed only 755 women and children that same year.

Providing safe transitional housing could greatly reduce victim deaths, and more: it could release thousands of children from captivity in an abusive household where the non-abusing partner lacks the resources to escape.

Of course, our own public resource constraints stand in the way; federal housing funds have been slashed, the Redevelopment Agency (long our largest source of affordable housing funds) has been eliminated and state bond funds exhausted. We need to think differently about how we find and build affordable housing in this challenging fiscal environment. In 2012, I proposed that the city study the conversion and renovation of several run-down motels — often the hotbeds of prostitution activity along North First Street, Monterrey Road and The Alameda — for affordable housing. The City’s Housing Department studied the issue, and determined that it offers a promising means to create housing at about half the cost of building housing traditionally. As Mayor, I’ll push forward with these and other initiatives to identify means to build more housing units for victims.

Finally, we can better coordinate our law enforcement responses with domestic violence social service providers. As with officers in the gang unit, SJPD’s Family Violence unit requires officers to possess highly specialized training, and to develop sensitivity to the intensely emotional and explosive realities of violence within the home. Learning curves are steep. Understanding what to do, for example, when dealing with a recanting victim — a very common phenomenon in victimization — requires an experienced detective, and our relatively brief shift rotations do not allow our residents to fully benefit from the expertise officers develop over their tenure. Officers in all other units — from patrol to gangs — would also benefit from more than the standard two hours of annual training. One service provider complained that patrol officers often aren’t aware of their services when coming into contact with a reporting victim, thereby missing opportunities to encourage the victim to find a path to safety. We can better incorporate service providers, criminal prosecutors, and judges in officer training, as each have valuable information and perspectives to offer.

It remains the case, however, that our SJPD officers do an exceptional job of responding to domestic violence in a context of severely reduced resources. As one prosecutor put it, the Family Violence unit “participates in the Domestic Violence Council, has a specialized investigative team to address the problem, responds swiftly to calls, serves emergency restraining orders, and works under the most dangerous conditions to combat domestic abuse.” For good work being performed by dedicated officers, we can all be grateful.

10. Improving Emergency Medical Response

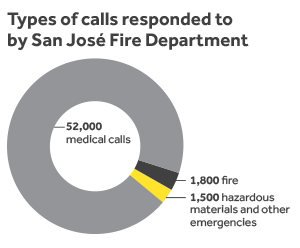

Timely emergency medical response constitutes a grave concern to all of us, but particularly for seniors who comprise a rapidly-growing source of demand for the service. As the number of our residents over-60, over-70, and over-80 continues to climb rapidly in San José, our needs for basic medical response for heart attacks, strokes, and falls will follow. We’ve already seen San José Fire Department (SJFD) medical call volume accelerate from 37,000 calls in 1995 to 52,000 today, largely due to the growing “Silver Tsunami” of our population.

Predictably, SJFD has struggled mightily to maintain emergency response times in the face of budgetary cuts and constraints in recent years. A drop in firefighter staffing has undermined our ability to maintain traditional standards for response times — that is, arriving at the scene of a medical emergency within 8 minutes 90 percent of the time or less. (Recent revelations about discrepancies in measuring and calculating response times suggest that “the good old days weren’t always good,” and the Department may have never met its standard response times, but that’s a much longer story.) Some County officials have made much of San José’s inadequate performance, withholding $2.1 million in funding for the Department — as if laying off more firefighters will improve the situation for our residents.

Rather than reverting to finger-pointing and cutting resources to our most critical life-savings services, we would do better to work together to improve emergency medical response.

THINKING AND DEPLOYING DIFFERENTLY: BEYOND “MINIMUM STAFFING”

As Mayor, I will push forward with significant changes to our current approach, beginning with the increased use of more nimble two-person medical response teams to respond to lower priority medical calls.

Based on data reported by the Fire Department to the City’s budget office, medical emergencies comprise 94% of the emergency calls to which our Fire Department responds. Although questions emerged in early 2014 about the reliability of that statistic, it remains incontrovertible that the great majority — and rapidly rising number — of emergency calls address medical needs. Like most urban fire departments, as the number of fires and fire fatalities has plunged in recent decades with dissemination of smoke detectors, building code changes and other safety improvements, the needs of our community have changed.

About 52,000 times per year, our Fire Department primarily serves as a medical emergency response agency. It also happens to be an agency that responds to fires (1,800 calls), along with hazardous materials calls and other emergencies (1,500). Yet our Department is staffed, built and operated to respond overwhelmingly to fires, primarily relying upon large, bulky and costly fire trucks and engines.

About 52,000 times per year, our Fire Department primarily serves as a medical emergency response agency. It also happens to be an agency that responds to fires (1,800 calls), along with hazardous materials calls and other emergencies (1,500). Yet our Department is staffed, built and operated to respond overwhelmingly to fires, primarily relying upon large, bulky and costly fire trucks and engines.

If anyone conceived of a plan to create an agency to respond quickly to a 911 calls for complaints of heart pain, nobody would suggest we use engines and trucks bearing four or five firefighters. We’d use SUV’s or vans, carrying a paramedic and a firefighter to respond quickly to the scene, and have additional personnel arrive as needed.

This is far from a new idea. Indeed, prior to 1991, according to former Chief Darryl Von Raesfeld, San José Fire Department responded to the majority of medical calls with two-person “light units.” Ten light units covered the areas surrounding those stations with the highest call volume, freeing the engines and trucks to respond primarily to fires.

In the early 1990s, changes came with fire union contracts that contained strict “minimum staffing” requirements, forcing deployments of larger vehicles and more personnel per vehicle. The fire union asserted that minimum staffing requirements protected the safety of personnel. Of course, the requirements also ensured that a thinly staffed fire department would not lose any firefighters, a sore spot for a fire union understandably frustrated over chronically thin staffing. With minimum staffing standards in place, city managers, mayors, and councils would recognize that any cuts to firefighter staffing would force the loss of entire engine companies — a much more difficult decision politically.

For many years, we’ve known this. City auditor reports from October of 2001 advised the City to shift to 2-person SUV’s for lower priority medical calls. Yet fire chiefs in San José — notably former Chief Von Raesfeld, who fought admirably for changes — have found their ability to adopt more nimble deployment strategies handcuffed by those minimum staffing requirements.