Our Money

Introduction

Big City mayors have the latitude to do a great many things that spur innovation and change, but the power to print money will never be one of them. Only the federal government can legally run chronic budgetary deficits. So, it “manufactures” money by selling bonds to cover trillion-dollar debts.

Cities, on the other hand, must balance their budgets each year. And that means mayors of cash-strapped cities need to honestly assess what services they can reasonably deliver within their means. What many politicians pitch as “bold visions” generally amount to “wish lists” without the money to actually accomplish anything. Smart leadership demands a vision we can afford, not promises that end up collecting dust.

I’ve long championed pension reform and fiscal responsibility. Two years before Measure B ever reached the ballot, I wrote an op-ed in the Mercury News arguing for pension reform. Fortunately, in 2012, the voters overwhelmingly approved Measure B, now saving taxpayers $25 million annually, while the remainder of the measure faces ongoing litigation.

But even if our retirement reforms were to survive judicial scrutiny, our fiscal problems would hardly disappear. San José would still face billions in unfunded liabilities in retiree benefits, even with solid economic growth. Our streets and our municipal buildings would still need hundreds of millions of dollars in maintenance and repair, more than $800 million to be exact. Even the most responsible approach to addressing these debts will require decades of fiscal discipline. And complicating matters could be a host of other potential burdens, including a major civil judgment against the City, a statewide downgrade of municipal bonds, or another recession. We face tough choices ahead.

Budgetary “quick fixes” don’t exist in the real world. People often reach for such ideas in times of uncertainty, and as this election will demonstrate, politicians exploit this wishful thinking by offering their fiscal panacea du jour.

But I believe there’s a more honest approach, one that recognizes that we collectively face huge burdens. Rather than attempting to offer a “quick fix,” I’ve laid out five principles, or “rules,” which will guide my budgetary decision-making as San José’s next mayor. While these rules should help steer us through difficult times, we must assume the City of San José will still not have enough money to provide the level of services we’d all prefer.

Simply, we have to be more resourceful, more cost-effective and more innovative.

Here’s how:

Rule #1: Find Partners—and Get Out of the Way

As San José struggled through painful service cuts and layoffs these last few years, it quickly became clear I’d need to look outside City Hall if I wanted to get much of anything done. So, I worked to identify key partners in the non-profit and private sector who were willing to take on tasks traditionally performed by the City. These tasks included helping the homeless find work and keeping alive a treasured community event like Christmas in the Park. Well-conceived partnerships can often improve services while reducing budgetary burdens on taxpayers. Opportunities about to engage in partnerships to build more sports fields, administer the City’s retirement funds, and preserve historic neighborhoods, among other priorities. [READ MORE HERE]

Rule #2: Moneyball—and Data—Isn’t Just for Baseball Fans

City leadership demands woefully little data to justify the large spending decisions routinely made by Council each year. This lack of rigor costs taxpayers millions. As mayor, I will push to implement the use of “Fresh Start Budgeting” to enable us to push the “reset” button on our budgetary decision-making. If we publicly vet every line item of spending in key departments, and better use quantitative tools like regression analysis, we can allocate our scarce dollars more effectively. We can create “open data” platforms, using software and technology, to better engage the public and improve our budgetary decision-making with data-based discipline. [READ MORE HERE]

Rule #3: Innovating in Times of Scarcity: If Necessity is the Mother of Invention, then Listen to Mom

Every day, organizations use innovative tools developed in Silicon Valley to improve performance, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. Particularly in times of budgetary scarcity, City Hall can do better to embrace the power of innovation to improve the ways that we serve our residents, whether that involves leveraging the latest technology, or restoring familiar but proven innovations, such as community policing. I’ve outlined several initiatives I’ll lead as mayor to improve public safety, reduce permitting delays, and expand our responsiveness to neighborhood needs. Each approach shares a common trait: leveraging the Valley’s own innovative energies and ideas. [READ MORE HERE]

Rule #4: The Rule of Holes: When You’ve Found Yourself in One, Stop Digging

Years before Measure B ever reached the ballot, I stood up for pension reform and fiscal responsibility, and I will continue to do so as mayor for a simple reason: our grandchildren should be able to decide how to spend their money. We shouldn’t spend it for them. We cannot continue to allow skyrocketing retirement costs—which have quadrupled in the last decade—to undermine our ability to pave streets and respond to emergencies. How we get past our budgetary burdens will depend on whether we have a mayor who will fully litigate—and implement—Measure B reforms, and ensure that we’re paying off our long-term obligations. Within my first year in office as mayor, I’ll push for full funding of our annual retiree healthcare obligations, to finally halt the growth of unfunded liabilities in that account. I’ll continue my efforts through the General Plan to stop the conversion of employment land and maintain the land for employment uses ensuring that future development will benefit the City’s—and not merely the developers’—financial position. [READ MORE HERE]

Rule #5: Don’t Just Think Outside the Box; Destroy the Box

More flexible, creative approaches to urban problems can help us stretch our scarce public dollars. Three examples of initiatives that I’ve been leading—to address homelessness, street cleaning, and park development—illustrate the kind of innovative leadership and ideas critical to helping San José thrive in the decade of budgetary scarcity that likely lies ahead. Finally, we’ll go a long way by no longer viewing our city employees as “part of the problem,” but as “the solution” to our fiscal problems: providing financial rewards for our employees’ good ideas about how we can save money, cut waste, and improve efficiency. [READ MORE HERE]

1.Find Partners — and Get Out of the Way

FROM NAPSTER TO COYOTE CREEK ENCAMPMENTS

One afternoon in 2009, Eileen Richardson walked into my office and sat down. Her casual attire belied her impressive private-sector resume. Eileen once served as CEO of Napster during its storied journey through the venture capital and tech industries. Eileen didn’t come to my office to discuss the latest smartphone gadgetry, however. I asked her to come to City Hall because I’d seen a story about her homeless clients in a local newspaper.

Several years ago, Eileen started a non-profit organization, Downtown Streets Team, that employed homeless people in Palo Alto’s shelters to clean and maintain streets and buildings. In exchange, the Streets Team members would earn vouchers for housing and food, beginning a path toward self-sufficiency. As Eileen peered out of my 18th story office window, I recall feeling awestruck by Eileen’s decision to depart the lucrative world of tech and venture capital for an alternative that was, in many ways, even riskier and more laden with obstacles to success. The opportunity to meet extraordinary people like Eileen makes my job immensely rewarding.

Several years ago, Eileen started a non-profit organization, Downtown Streets Team, that employed homeless people in Palo Alto’s shelters to clean and maintain streets and buildings. In exchange, the Streets Team members would earn vouchers for housing and food, beginning a path toward self-sufficiency. As Eileen peered out of my 18th story office window, I recall feeling awestruck by Eileen’s decision to depart the lucrative world of tech and venture capital for an alternative that was, in many ways, even riskier and more laden with obstacles to success. The opportunity to meet extraordinary people like Eileen makes my job immensely rewarding.

I asked Eileen to meet because San José faces a palpable catastrophe in its creeks, which have hundreds of people living in them. With the onslaught of the Great Recession in 2008, the numbers of homeless encampments along the shores of Coyote Creek and the Guadalupe River mushroomed, and entire villages of hundreds of homeless residents sprung up in locations bearing dehumanizing names like “The Jungle.” Beyond the obvious human toll of homelessness, the encampments leave a massive environmental impact in their wake, with human and biological waste, needles, non-biodegradable plastic and other substances polluting the water — which eventually feed the San Francisco Bay. Beyond the waste problem, the encampments exacerbate the erosion of riverbanks and creek beds.

Traditional approaches to dealing with homeless encampments have failed to gain traction. Some of my colleagues argued that we simply direct police officers to go into the creek beds and arrest all of the campers for trespassing. Of course, that assumes that we have enough police officers to engage in an endless “whack-a-mole” strategy with the homeless. The homeless return after their day in jail. We know well the pitfalls of a lock-em-up strategy: it costs taxpayers at least $45,000 per year to house a single inmate in County jail, but permanent housing in a single-room-occupancy apartment unit costs about $21,000. We also spend as much as $80,000 on a single large creek encampment sweep for police officers, Housing Department outreach workers and demolition crews to remove the “self-made” housing in the creeks. Three days later, the homeless return. The City of San José has been Sisyphus, rolling the mythical rock to the peak of the mountain, only to see it roll back down the hill.

Eileen and I talked for about an hour in my office that day. I asked if she could launch her remarkable “work-first” model in the creeks of San José. She asked me if the City had any money. I said, “No.” Eileen said: “Yeah, we’ll do it.”

So, our adventure began. Our creative City staff identified grant funding from the EPA to clean polluted creeks. Leveraging additional assistance from the Santa Clara Valley Water District — which already funded creek cleanups — and a private grant from the eBay Foundation, we launched. The City’s effort appeared focused on removing bureaucratic obstacles. If EPA grant guidelines restricted their funding from being used to provide housing, we’d find a legal way to use the same money to fund cleanup work.

A year and a half later, Downtown Streets Team (DST) has moved over fifty homeless creek-dwellers into permanent housing. Dozens more have begun working full-time, beginning their journey to selfsufficiency. A star was born. DST has now spread to a half-dozen cities in the Bay Area, with many more welcoming them in.

To be sure, much, much more work remains to address the enormity of San José’s homelessness problem and reclaim our polluted creeks, still dotted with encampments. Although the official tally puts the number around 8,000, unofficial sources estimate that our County may have as many as 12,000 homeless people. Much need has gone unfilled and much work remains.

Yet, we also see the promise of this untraditional model. If we can expand this approach and incorporate more partners, we can take on more of the problem. A company or affluent neighborhood, frustrated with homeless encampments nearby, could pay a fee to DST to come into their community to work with those homeless. I’ll explore one such promising initiative, “San José Gateways,” in the next chapter. Even when tough times deplete municipal budgets, they don’t undermine creative ideas. A first step to dealing with budgetary shortfalls is to find ways to do things differently.

SAVING SANTA AND SEDUCING SILICON VALLEY

Sometimes, that just means finding different people to do those things.

The Downtown’s winter holiday events — Christmas in the Park, Downtown Ice (the ice rink beneath the palms filled with children each December) and Winter Wonderland — attract over a half-million children and parents to San José’s downtown every year. Beyond providing an opportunity for community gathering, the events also fill Downtown cafés, restaurants, shops and movie theaters during an otherwise difficult time for those merchants.

When the City had to cut its quarter-million dollar subsidy to Christmas in the Park in 2010, many foresaw its demise. Hundreds of volunteers worked tirelessly every year to put on the festival, but until the organization hired a full-time executive director in 2012, it lacked the capacity to fundraise to fill the hole left by the City’s pullout.

I rolled up my sleeves with Silicon Valley Leadership Group CEO Carl Guardino. We asked Mayor Reed to co-host a fundraiser, invited donors, hit the phones for three months and raised over $180,000 in sponsorships that year to keep the events rolling.

While we all patted ourselves on the back, Carl and I knew that it wasn’t sustainable. We needed to find a way to keep the events running, because it wouldn’t take long before our wallet-weary friends stopped answering our calls.

Carl came up with a creative alternative: the Santa Run. We hustled companies for multi-year sponsorships to support a healthy running or walking event, with a uniquely fun concept: provide every runner with a Santa outfit. Within a half-decade, we vowed to break the world record for the most “running Santas” in any place. I called the civicminded executives of several local employers, like TiVo, Acer and Ernst & Young, who cheerily agreed to sponsor the event. Ragan Henninger, who was on my staff, did plenty of the heavy lifting, cutting through red tape, obtaining permits and reducing overblown fees to ensure that sponsor dollars remained focused on the benefit.

Carl came up with a creative alternative: the Santa Run. We hustled companies for multi-year sponsorships to support a healthy running or walking event, with a uniquely fun concept: provide every runner with a Santa outfit. Within a half-decade, we vowed to break the world record for the most “running Santas” in any place. I called the civicminded executives of several local employers, like TiVo, Acer and Ernst & Young, who cheerily agreed to sponsor the event. Ragan Henninger, who was on my staff, did plenty of the heavy lifting, cutting through red tape, obtaining permits and reducing overblown fees to ensure that sponsor dollars remained focused on the benefit.

In our first year in 2012, we exceeded our goals for entrants and fundraising. Equally important, the spectacle of 3,000 Santas running down Almaden Avenue created an iconic memory for every observer. The Santas chased a “Grinch” — played by good sport and County Assessor, Larry Stone — in the lead car, and ran into a finish line surrounded with snow machines, blowing flakes on the finishers. Upon completing the five-kilometer race, the Santas were greeted by (what else?) cookies and milk.

NEW PARTNERSHIPS

As the Great Recession dragged on through my term in office, I continued to seize new opportunities for partnerships. We had to seek partners outside of City Hall to help us accomplish tasks that were previously taxpayer-funded. With homework centers depleted from state cuts, and city-funded after-school programs vastly diminished, I worked with the Silicon Valley Leadership Group to launch “1000 Hearts for 1000 Minds” to link local company employees to struggling public school students, engaging respected non-profits like YMCA and Reading Partners to expand tutoring in math, science and reading. We’ve already matched almost 500 adults to kids in these tutoring programs throughout San José and the Valley.

With the state-mandated elimination of the Redevelopment Agency, I worked with Kim Walesh and private sector leaders like UBS executive Rich Braugh, hotelier Michael Mulcahy and Business Journal publisher James MacGregor to enlist local business executives to engage in peer-to-peer conversations over dinner or lunch with CEOs who were considering moving their company headquarters to San José. We found — to nobody’s surprise — that corporate executives found the voices of their private-sector peers to be far more credible than those of a government official or broker making a “pitch” to come here. Those conversations also helped to provide an “in” for city officials to better explain San José’s set of incentives and value propositions. One set of such conversations, with BJ Jenkins, the CEO of Barracuda Networks, helped to encourage a decision to launch Barracuda’s new manufacturing plant in South San José, employing hundreds of workers.

PARTNERING IN THE FUTURE

Through these and other partnerships, it became increasingly clear that we could still accomplish great things amid budgetary scarcity. Ample other opportunities exist for us to find partners to do what City Hall is doing — or to do it better. We lack Planning staff to conduct surveys to protect our historic buildings and other assets — despite 58 having ample funds contributed by developers years ago for the task. We could rely upon able non-profits like History San José or the Preservation Action Council to administer those contracts. We can also better partner with our school districts, as I describe in a later chapter, to expand the availability of sports fields to kids and adults.

More opportunities abound. By engaging in creative partnerships, the City can do more with less — and in some cases, the City could be doing something rather than nothing.

2. Moneyball — and Data — Isn’t Just for Baseball Fans

STEPHEN COLBERT: INCUBATING “TRUTHINESS”

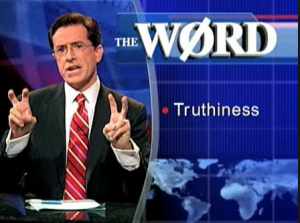

Humorist Stephen Colbert famously urges viewers to “feel the truth,” rather than consulting books and data to discern “heartless facts.” “Anyone can read the news to you; I promise to feel the news at you,” Colbert implored. Far more than any “facts” that might occupy our brain, Colbert urged us to rely on our “gut” to guide political decision-making by its “truthiness.”1

Humorist Stephen Colbert famously urges viewers to “feel the truth,” rather than consulting books and data to discern “heartless facts.” “Anyone can read the news to you; I promise to feel the news at you,” Colbert implored. Far more than any “facts” that might occupy our brain, Colbert urged us to rely on our “gut” to guide political decision-making by its “truthiness.”1

Colbert should feel reassured that he has succeeded, because “truthiness” governs decision-making in City Hall as well — particularly in the absence of data.

In the decades of the Redevelopment Agency’s tenure in San José, too often the “truthiness” of an appealing expenditure trumped common sense in allocating scarce public dollars. Few examples seem as prominent as the $32 million spent on business “incubators” over two decades by the San José Redevelopment Agency (RDA), on which the San José City Council served as the governing board.

Incubators are launching pads for small tech-focused businesses, providing professional and business services to small companies looking to launch. Many privately-funded incubators — ranging from Y Combinator, to Plug & Play, to in-house incubators at prominent venture capital firms like Kleiner Perkins — have launched famous Silicon Valley brands. Incubators are a great concept — and often a successful one — particularly when implemented by business-savvy venture capitalists or by tech-focused research labs.

Of course, City Hall is neither. Government-funded incubators are controversial, and the City of San José led the charge to launch several incubators over the course of two decades — the BioCenter, Software Business Cluster, Environmental Business Center and U.S. Market Center — with the assistance of $32 million in RDA money, in partnership with the San José State University Foundation (SJSURF). In Council committee hearings and in press releases, we were told that companies housed in the incubators generated $1.2 million in annual tax revenue, and that 70% of the graduating companies filled empty office or industrial space in San José. We were told of countless awards and distinctions garnered by the incubators. We were told of Callidus Software, the exemplary “success story,” which hired hundreds of Bay Area employees since its launch. For years, the City Council bought the story: these incubators were a shining success story for San José.

I began to learn otherwise one winter evening in 2010 at a reception in a Palo Alto hotel. As I meandered through a crowd of venture capitalists and tech business executives, I stopped to talk to anyone who would listen about the benefits of starting their innovative business in one of San José’s incubators. As I eagerly pitched entrepreneurs, funders and university researchers, I parroted all that I’d been repeatedly told in City Hall about the incubators’ extraordinary success. I bored the attendees with my sales pitch.

Sadly, my sales pitch had one additional flaw: nobody believed it.

That is, in this group of highly sophisticated venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, nobody had ever heard of our incubators. As that fact became increasingly apparent with each succeeding conversation, my confidence in the success — and the significance — of the City’s incubator program waned.

I began asking questions of my own to staff. For example: why would the City and RDA entrust the management of a BioCenter incubator to a university foundation that had no connection to any hospital, medical school or prominent biomedical research institute? Why aren’t we asking companies why they’re leaving the incubators, or how we can keep them in San José?

In Council committee hearings, when I asked for data supporting the claims of the incubators’ outstanding success, I received none. At a June 2011 RDA hearing, the Council considered whether to spend another $400,000 in RDA funds to pay for the lease on a biotech incubator. I raised questions about discrepancies in jobs data and apparent conflicts of interest. Several colleagues jumped to the defense of the well-connected executive directors of the incubators, one deeming my “cross-examination” to be “inappropriate.”

Media covering that hearing started to shake things up. I began to receive phone calls, most from people who didn’t want to be identified publicly. Past board members, company sponsors, former RDA employees, venture capitalists and others all shared the same troubling viewpoint: the incubator emperor was wearing no clothes. As with Aesop’s fable, however, no one wanted to be the kid who would actually say so publicly.

One person familiar with City Hall told me of “the reports.”

“What reports?” I asked.

“Well, they’ve been buried,” the caller responded. “They’ve never been shown to Council. They’re not flattering, either to the RDA, or to SJSURF.”

Sure enough, consultants contracted by the RDA had evaluated the incubators, and their reports sat in the RDA’s voluminous files — but were never disclosed publicly, or to Council. The incubators’ persistent deficits compelled the authors of a 2007 report to urge new management to supplant the SJSURF, to better leverage external financial support. In 2009, three independent consultants prepared a report with even less flattering findings:2

- After $32 million in investment in taxpayer dollars, the City of San José received less than $200,000 annually in tax revenues from participating companies;

- By 2011, graduate companies had created only 150 jobs in San José over the prior decade and a half;

- Only 11% of the graduating companies actually occupied space within the city of San José;

- SJSURF failed to monitor its tenants, or to adequately supervise the contractors managing the incubators, despite specific contractual requirements to do so. Fifty-eight percent (58%) of tenant companies failed to even obtain a business license in the City of San José.

As I probed further, it only got worse. At least one of the private incubator managers, who contracted with SJSURF, took an investment position in the tenant companies on her own private account — while managing the other tenants. The palpable conflict of interest apparently didn’t worry her. The same manager also received consulting fees to help other cities build biotech incubators to compete with San José’s. Fortunately for us, she did about as well for those cities as she did for San José.

Staff and my Council colleagues held their ground, pointing to one successful start-up in particular, Callidus Software, as a “poster child” of incubated success. The company fled San José for Pleasanton in 2010, however, taking their jobs and tax revenue with them. When I spoke with a former senior executive at Callidus about his experience within the RDA’s Software Business Cluster, he responded bluntly: “When they hired me, we all agreed that we needed to leave the incubator quickly.”

I urged an audit, and that we cut off future funding. The Mercury News editorial board agreed, prodding the Council to lift the veil on this buried report and its cover-up.3

Nonetheless, the majority of the Council expressed little interest in further scrutiny. Cozy relationships prevailed among executive directors, board members, Council and RDA staff. Some believed that RDA funding was tapped out anyway, so we could conveniently allow the whole issue to die. Remarkably, few on the Council felt sufficiently indignant to want anyone to be held accountable, perhaps because sufficient embarrassment had already resulted with the surfacing of these reports. The program dissolved the following year.

IN GOD WE TRUST; ALL OTHERS BRING DATA

Why did the incubator program persist for so long? How could we spend $32 million on a program without better vetting its weaknesses?

When we decline to rigorously ask questions and demand facts, and instead rely on unfounded, timeworn assumptions founded in “truthiness,” we will get burned. As I hear occasionally from a tech-employed peer, “In God We Trust; all others bring data.”

It seems self-evident that the City should make budgetary decisions by relying on data about the cost-effectiveness of the programs in which we’re investing scarce taxpayer dollars. Yet data-driven decisionmaking appears vastly undervalued role in public sector budgeting. Former White House budget directors Peter Orzag and John Bridgeland recently groused about the federal budgetary process stating Washington’s “spending decisions are largely based on good intentions, inertia, hunches, partisan politics, and personal relationships.”4

We should not be surprised, then, when money appears wasted by underperforming programs or poorly implemented initiatives.

While many within City Hall will jump to object that the City of San José has a long tradition of utilizing hard analysis in its budgetary decisions, I have observed plenty of examples where “truthiness” and wishful thinking prevailed over data-driven decision-making:

- For decades, councilmembers sat on our City’s pension boards with union-appointed employees, and the boards routinely signed off on unrealistically optimistic assumptions that actuaries relied upon to calculate assets and liabilities of those retirement funds. For example, by pretending that the fund could consistently earn an investment rate of return of 8% (or 8.9%, if one includes administrative costs), the funds looked flush. Of course, private sector pension funds like Warren Buffet’s — who has considerably more success investing than the City — assumed far lower rates at the time. Nonetheless, rosy assumptions enabled union members and the City to avoid confronting the billions in unfunded liabilities in the retirement accounts created by their actual costs. The mayor appointed Councilmembers Rose Herrera, Pete Constant and me to pension boards in 2008 to push for greater accountability, and we ultimately succeeded in requiring the appointment of qualified financial professionals to take our seats on the Boards.

- Before I came into office in 2007, the Council attempted to play the role of “amateur venture capitalist” with public money through what was known as the “Catalyst Fund.” I twice voted against it, noting that even highly regarded venture capitalists typically lose far more often than they hit the jackpot. Through the Fund, the Council used taxpayer dollars to take high-risk equity positions in local companies, losing several hundred thousand dollars. With the helpful push from my similarly incensed colleague, Rose Herrera, we successfully pushed to dissolve the Fund in 2010.5

- Between 2008 and 2010, I spoke out repeatedly against the RDA’s overly optimistic revenue forecasts in its proposed budgets. RDA staff relied on paid consultants to create estimates of tax increment growth, but repeatedly “encouraged” them to make aggressive assumptions on growth to support the Agency’s ambitious spending plan. As I repeatedly argued, the consultants’ projections for growth in property valuations greatly exceeded those of the County Assessor and ran contrary to the prevailing economic wisdom of the day. Sadly, in each one of the three years, my warnings of inflated projections materialized, leaving the RDA underwater on its commitments and imposing millions in costs on the City’s General Fund.

- In 2008, I publicly questioned the proposed expenditure of $350 million on a convention center expansion. A Brookings Institute study revealed that, after two decades, the national convention and conference industry had not grown at all. It seemed foolhardy to bet a third of a billion public dollars in the hope that growth would reemerge after a generation-long absence, particularly where new technologies like telepresence seemed destined to cut into convention business. Project proponents bristled at my (already dated) suggestion in the Mercury News that we were spending millions on an “expanded hula-hoop factory when the kids are using Playstations.” Eventually, the Council agreed to shrink the project by two-thirds when financing limitations became more apparent, and a more modest expansion was successfully completed — under budget — in September of 2013.

- Although the majority of the Council typically rubber-stamped the budgets, funding requests and scope of authority sought by the politically powerful Team San José (TSJ) — the contractor managing our convention and cultural facilities — I increasingly objected amid reports of rising costs and worsening balance sheets.6 At my urging in 2010, after TSJ’s prior management posted a $7 million loss, the City Auditor probed into unwarranted bonus payouts to TSJ executives, ballooning costs and shrinking regional market share.7 The revelations prompted leadership changes on TSJ’s board and front office.

In each of these instances, data-driven decision-making could have saved the Council from poor decision-making. Where the Council or the City staff stuck with “truthiness,” we — and the taxpayers — paid a price.

MONEYBALL AND CITY HALL

Billy Beane is the General Manager for the Oakland A’s. References to major league baseball will typically put half of anyone’s audience to sleep, but after all, we’re talking about the budget here — I’ll presume that we’ve already got plenty of folks nodding off.

Billy Beane is the General Manager for the Oakland A’s. References to major league baseball will typically put half of anyone’s audience to sleep, but after all, we’re talking about the budget here — I’ll presume that we’ve already got plenty of folks nodding off.

Beane famously captured the imaginations of baseball fans with his wonkish approach to selecting baseball players in the early 2000s, which became known as “Moneyball.”

The small-market Oakland A’s routinely compete against teams with payrolls three to four times that of the A’s (with its younger and undistinguished players). Remarkably, over the last dozen years of Beane’s tenure, the A’s have won more games than almost any team in the League (only the Yankees and Red Sox have won more), largely with a collection of no-name rookies and rejected veterans. Beane has since been immortalized by Brad Pitt in a major motion picture, Moneyball, based upon a Michael Lewis eponymous best-seller (I expect Pitt will also play my role when film production begins on the long-awaited movie release of this book).

Beane’s secret? He didn’t accept the typical off-the-cuff “expertise” of Major League scouts touting players had the “best-looking swing” or the “toughest curve ball.” He focused on data. He didn’t focus on just any data, either. Any eight year old in the Bronx can recite the annual home run totals and batting average for Alex Rodriguez. Beane identified less traditional measures that had greater correlations to outcomes; rather than batting average, on-base percentage better predicted a team’s run-scoring ability. Scrutinizing the data, he routinely found low-salary players who could score more or pitch better than the high-priced free agents.

Two former White House budget officials — Peter Orzag and John Bridgeland — provocatively asked an important question in the title of a June 2013 issue of The Atlantic, “Can Government Play Moneyball?” While Orzag and Bridgeland targeted the federal government, their point is a broadly applicable one in the public sector, where incremental budgeting tends to insulate poorly performing programs from scrutiny, perpetuating suboptimal spending patterns. Zero-Based Budgeting and other innovations have sought to force these seemingly unconscious decisions into the light of public scrutiny, but for various reasons, have not taken hold broadly.

As I learned long ago, math is the language of policy analysis. It enables us to reach relatively objective conclusions before we inject value judgments about what’s best — so that we can have a fair conversation about how we best effectuate those values. Private sector decision-makers don’t invest hundreds of millions of shareholder dollars on a gut instinct. They do the analysis, for example, to know whether the stock price of a takeover target appears overly-hyped inflated or a bargain.

Yet in City Hall, we don’t see quantitative policy analysis of even a modest level of sophistication. You’d be hard-pressed to find a single staff or consultant report in City Hall that utilizes a common tool known as regression analysis. Regression is a mathematical method that enables economists to identify which factors might independently have stronger or weaker influence over a particular outcome. This is particularly valuable in a complex world where outcomes have multiple causes.

Why might the City need to rely on that tool? Here’s one example: we spend millions of dollars fighting gang violence, through the police, gang prevention, gang intervention and gang suppression programs. Regression analysis could help shed light on whether reductions in gang violence appear more strongly correlated to changing police tactics, expenditures on gang prevention programs or simply the start of the school year. If we have scarce dollars to devote to a difficult problem like gang crime, shouldn’t we want to know where those dollars can be spent most effectively?

I’m not suggesting that numbers and data should supplant our good judgment about how to best spend the public’s dollars. Nobody wants heartless, nihilistic robots to represent them on the Council. Ultimately, budgetary decisions reflect our values, and human wisdom is the best tool of all.

But the lack of data-driven rigor undermines our ability to focus our scarce resources to best effectuate those common values. We all value violence prevention, but what’s the most cost-effective path to doing so? We all agree in the importance of literacy, but if we could more efficiently use technology to help adults to read in our libraries, wouldn’t we all agree to use the savings to help more adults read to their kids? By asking these questions, we can achieve better results.

“RESET BUDGETING”

Finally, the lack of rigor in budget decision-making becomes most apparent every June during the council’s budgetary deliberations. Councilmembers issue a flurry of memos to address small portions of the budget — a hundred thousand dollars to keep a library open on Saturdays, or $180,000 to hire a couple more park rangers, for example — but close to 99% of the roughly $2.5 billion budget goes largely unscrutinized.

Why? Incremental budgeting. That is, every year, the City Manager instructs each of the City’s department heads to assume that their budgets will grow, say, 2%, or be cut, say, 1.5%. Each director will then submit a proposed budget to the City Manager that looks nearly identical to last year’s budget — with a description only of the incremental or decremental changes. The public, media and Council see only those changes — which positions are added or subtracted, and how much they will cost.

What remains hidden beneath the waterline is the great mass of the iceberg. The rest of the budget will be “approved like last year’s,” and is seldom questioned. Occasionally, someone will raise a question about the rest of the iceberg. It’s nice to add positions in community centers, for example, but how do we justify what we’re already spending in community centers? Should we be spending more or less on one program? Should we completely eliminate an underperforming program, so we can fund something else? Those questions go largely unanswered in the current process.

In my experience, government’s worst decisions tend to be those decisions that aren’t made. “Default” choices pose a unique danger, because they’re the least transparent to the public. Our highest priorities are undermined where the City inattentively spends money on programs having little to do with our residents’ priorities.

As mayor, I would hit the “reset” button. This requires what I call “Reset Budgeting” — a variant of a concept developed a couple of decades ago, called “zero-based budgeting.” Both concepts require that we begin each year at zero. We don’t look to last year’s budget for next year’s authorization of the Department of Transportation or the Library Department spending. We look at “zero.” We start by assuming no open libraries, no repaving, no streetlight repairs.

Now, what do we value? What do we prioritize? Reset Budgeting requires us to begin with those very difficult questions, and to do so publicly.

Of course, nobody believes that the City Council can do this for every single department during every annual budget hearings. It’s very time-consuming, work-intensive, and it could harden bureaucratic gridlock. Moreover, some spending is specifically mandated by federal or state law, such as the use of airport landing fees or utility undergrounding charges. That’s why I don’t propose a standard “zero-based budgeting” approach.

Instead, we should pick our spots, and rotate our scrutiny. If we focus Reset Budgeting where the Council has meaningful flexibility to use dollars, we can ensure that the discretionary portion of every major department is “scrubbed” with a Reset Budgeting approach, say, every 5 years. Rotating Reset Budgeting from one department to another each year will force a public discussion of priorities largely lacking in civic discourse in this city — and nearly every other city.

Further, we should engage our City Auditor’s Department in the “scrubbing.” A recent audit of our Library Department found some $1.5 million in potential savings in improved deployment and assignment of staff, for example. Those savings could enable us to open our libraries additional hours to better serve our public citywide, such as by opening every one of our 25 branches on Saturdays. Coordinated with Reset Budgeting, audits can boost performance and better prioritize spending all at once.

In the meantime, in each year’s budget, we should make public every line item in every Department, so even if there’s not debate on the floor of the Council Chambers, there can be public scrutiny of every dollar. We can save the printing costs by posting it all on-line. Opportunities emerge where residents can engage with us, exploring how we can save money by leveraging their creativity and resourcefulness. We could host on-line “study sessions” to solicit ideas about more efficient approaches to spending and service delivery. It all requires, however, that we have the courage to allow the public a peek “under the hood.”

By routinely lifting the hood, we can both better engage the public, and make decisions that better reflect our highest priorities. After all, isn’t that the real purpose of a budget?

OPEN DATA

Finally, as I discuss further below, we can leverage public engagement to help us better use data to improve our decision-making if we make that data public. Creating “open data” platforms that San José’s many amateur and professional software developers can utilize to help City Hall improve the cost efficiency in its delivery of services and projects. For example, consider how we might post budgetary data regarding code enforcement, along with raw data around the number, type, location and compliance rate of various code enforcement citations. Savvy app developers could help us better understand whether we can better address neglect by deploying code enforcement officials proactively at different times or neighborhoods to enable us to address blight and generate revenues that could better sustain the program.

All of this provides an appropriate transition to a broader discussion about how we can leverage technology and innovation to spend our scarce dollars smarter.

3. Innovating in Times of Scarcity: If Necessity is the Mother of Invention, Then Listen to Mom

Strong leadership recognizes the opportunity in every crisis. Our fiscal challenges present us with the ability to think differently about how we serve and protect our residents.

Taking a few steps outside City Hall, we can learn the lessons from the extraordinary innovation all around us in Silicon Valley, and we can forge a path to better services and a safer city. Innovation can help make San José safer, better served, and, through it all, more cost-effective.

CROWD-SOURCING FIXES – AND BUDGETARY DECISIONS

Another innovative way of engaging the public in budgetary processes — called “participatory budgeting” — has gained adherents in cities throughout the world where it has been tried.

San José has a wealth of community-minded leaders who deeply engage in supporting their city through their volunteer energy, organizing clean-ups, tree-plantings and graffiti removal efforts on one weekend or another. Some — like Parks Foundation Executive Director James Reber or CommUniverCity community director Imelda Rodriguez — leverage sophisticated partnerships with non-profit organizations to build new playground equipment with a team of volunteers, or with corporate foundations to improve health outcomes. Others, like Graham and Sandra Stichman, simply encourage their neighbors to join them once a week to pick fruit from participating neighbors’ yards to donate to a local food bank.

San José has a wealth of community-minded leaders who deeply engage in supporting their city through their volunteer energy, organizing clean-ups, tree-plantings and graffiti removal efforts on one weekend or another. Some — like Parks Foundation Executive Director James Reber or CommUniverCity community director Imelda Rodriguez — leverage sophisticated partnerships with non-profit organizations to build new playground equipment with a team of volunteers, or with corporate foundations to improve health outcomes. Others, like Graham and Sandra Stichman, simply encourage their neighbors to join them once a week to pick fruit from participating neighbors’ yards to donate to a local food bank.

Very often, I hear of creative ideas from our neighborhood leaders and community advocates about how we could “do more with less.” I’ve often acted on that advice, for example, to secure the availability of a city truck and driver to provide tools and collect garbage to support Saturday neighborhood volunteer clean-up projects. The logic seems incontrovertible: a few hours of a single city staff person can leverage thousands of hours of many volunteers, and we’ll all benefit from the result.

How can we better leverage that community energy to make our scarce public dollars more effective?

From the town of Puerto Allegre, Brazil, a concept known as “Participatory Budgeting” has emerged. It has since spread to 1,500 cities including San Francisco, Chicago and New York. The notion is simple: by identifying a restricted pot of funding for community-specific projects, we can empower local communities to directly determine the expenditure of small amounts of public dollars for relatively small, discrete projects of significance to the community. Interested residents gather through an agreed-upon public process, vote on their highest priorities and the local council or board allocates the money accordingly. Some residents will push to improve a pedestrian crossing with a flashing beacon in front of a school or senior center. Others will seek to improve the drainage in a frequently flooded park or improve the lighting on a crime-ridden street. Research on participatory budgeting demonstrates many positive benefits, including more community engagement and increased social interaction in neighborhoods.

Most interestingly, the research also shows that well-designed participatory budgeting approaches can stretch public dollars farther. Why? Neighborhood and community leaders are very resourceful. They persuade their neighbors to volunteer. They hustle their tech employers and their company foundations for grants. With volunteers and matching dollars, they get park benches fixed, install playground equipment, trim hedges and clean graffiti without red tape and bureaucratic delay.

We can leverage their energy, their volunteer time and their grant dollars by allocating very small amounts of city dollars, with much greater impact. An effective participatory budgeting process can prioritize funding for those projects that best “leverage” the volunteer time, energy and dollars with public dollars, to ensure that we can do more with less.

Technology can help as well. On-line tools, like NextDoor, can make an on-line public decision-making process more transparent and less clumsy. Other tools, like See-Click-Fix, can geo-tag data from resident complaints, to enable residents to visually observe a map identifying the area’s most frequent gripes. City staff and local residents can better understand whether people are most concerned about a replacing a streetlight, or about installing a surveillance camera near a corner liquor store that attracts a lot of gang members. In either case, they can allocate resources to the items deemed highest need with some objective data to help guide their decisions. By enabling everyone in a community to see the priorities of their neighbors, volunteer groups can better mobilize to fix what they can without the City and to better organize for public resources where they need them.

All of this can start with a relatively small allocation of public funding — as little $100,000 per council district, a quantity smaller than the mayor routinely makes available for Council-directed funding priorities in each budget cycle. Of course, the mayor and the Council would have to agree to cede control of this small pot of funding, to allow our residents to make decisions for themselves.

Are there risks? Of course — nobody said democracy was free, or without risk. Council can contain the risk by starting small, allocating a small amount of funding initially allows us to learn and adjust. Within a couple of years, we’ll see that a participatory budgeting process can stretch our scarce public dollars much farther, and we can carefully make larger investments.

Beyond the dollars and cents, participatory budgeting brings other benefits. Residents engage with one another about their concerns. We build relationships in communities where stakeho lders might otherwise have little motive to get to know their neighbors. Social capital builds, and neighborhood safety often improves. Residents also become more sophisticated about the real costs, and real impacts, of budgetary choices. The mantra of “the City should just install one of those… [x, y, z]” to solve every local problem starts to disappear because neighborhood leaders become more savvy about the costs, and benefits, of various options. Community leaders become more focused, well informed and effective in getting what their neighborhoods need from City Hall.

4. The Rule of Holes: When You Find Yourself in One, Stop Digging

The “Rule of Holes,” of course, only applies to those of us unfortunate enough to land in one. That described the experience of those of us who took office in January of 2007. In my first weeks on the job, I learned that rule changes by GASB, the organization governing national accounting standards, would force cities throughout the country to more clearly disclose the status of their retirement accounts. City staff widely disclosed, for the first time, that it faced an unfunded obligation of $1.6 billion to pay for medical care for its retirees.

The “Rule of Holes,” of course, only applies to those of us unfortunate enough to land in one. That described the experience of those of us who took office in January of 2007. In my first weeks on the job, I learned that rule changes by GASB, the organization governing national accounting standards, would force cities throughout the country to more clearly disclose the status of their retirement accounts. City staff widely disclosed, for the first time, that it faced an unfunded obligation of $1.6 billion to pay for medical care for its retirees.

That is, taking all of the contributions to the retirement fund by city employees and taxpayers, after assuming an 8% annual growth from investments (a wildly optimistic assumption, as we’d soon learn) and additional contributions over the years, we’d still end up $1.6 billion short after 30 years of paying out medical benefits to our retirees. And here was worse news: that didn’t even count our pension obligations. Sure enough, within a few months, we would find ourselves in the worst recession in three-quarters of a century. The stock market losses sank portfolios throughout the country, wiping out life savings and retirement funds. The following year, the toll of those shortfalls fully exposed the foolishness of the steadfast optimism of the San José retirement boards in their fund returns (which the two boards estimated at 8% and 8.25%, rates twice as high as many private sector company retirement funds).

Mayor Reed appointed me to the Police and Fire pension board to help fix the problem, and I immediately began pushing for more transparent, realistic accounting of our assumptions and pension obligations. Two years before a pension reform measure reached the ballot in 2012, I wrote an op-ed in the Mercury News, arguing for pension reform and reducing benefits for new hires.8 As mayor, I’ll continue to push forward for fiscal reforms.

The problem, of course, is that we’re still in that hole. And it’s a big one: $3 billion in unfunded retirement obligations alone. What, exactly, do we do about it in the coming decade?

STEP ONE: STOP SPENDING OUR GRANDCHILDREN’S MONEY

Although we’ve made great progress under Mayor Reed — particularly if we successfully push Measure B’s reforms over the goal line — we still have much work to do. As with any credit card obligation, our failure to pay any “required minimum” on our unfunded liabilities subjects the balance to compounding interest, making our debts grow.

Our retirement obligations are divided in two basic categories: pensions and retiree healthcare. Most of the public debate around retirement benefits in the media focuses on pensions. Most taxpayers remain unaware that the scale of our billion-dollar unfunded liabilities for retiree healthcare rivals that of our pension benefits.

Although San José now pays its full pension obligations annually, we don’t do so on the retiree healthcare side. In other words, some portion of the annual cost of retiree medical care is still subsidized by our children.

Why? Our willingness to “lift the veil” on our enormous unfunded liabilities in the City’s retirement accounts has forced us to take some tough medicine in the form of sharply rising contribution rates to pay off these obligations. On the healthcare side, both the city and the employees have the responsibility of paying the annual tab for retiree healthcare plans, and spike in contribution rates was causing most employees’ take-home paychecks to shrink precipitously. To soften the blow, the City agreed to cap the annual contribution rate increase for our police and firefighters. The difference between what was getting paid — “the cap” — and what the actuaries told us had to be paid — the “annual required contribution” — was simply added to the growing debt.

As mayor, I will push to ensure that that City pay its annual bill for retiree healthcare. Our children and grandchildren shouldn’t have to bear the burden of our debts.

STEP TWO: PRESERVE EMPLOYMENT LAND FOR OUR LONG-TERM FISCAL BENEFIT

San José is the only major city in the United States with a smaller population in the daytime than the nighttime. More typically, major cities are job centers. San José, in contrast, is the bedroom community for the rest of the Valley.

There are enormous fiscal implications in this jobs-to-housing imbalance. Why? Employers pay far more in taxes — taxes on everything from sales, utility, business licenses, TOT and assessed valuations of land, plant and equipment — than they consume in revenues. Residents certainly pay plenty of taxes, but most of those revenues go elsewhere, such as the County, the school districts or the state. Services to residents cost money. So, housing generally doesn’t “pay its way” in supporting the General Fund, unless the housing has exceptionally high value (e.g., millions of dollars per parcel) or exceptionally high densities (e.g., a high-rise in Downtown San José), where property taxes can exceed the service delivery costs.

So, taxpayers do better fiscally by having more employers, and fewer residents, in their city. That is, they receive better services for whatever taxes they’re paying. For that reason, politician after politician in San José has long bemoaned what is known and San José’s perilously low “jobs-to-employed-resident ratio.” That statistic, which has long hovered around 0.85 or less in San José, compares with jobs-to-employed resident ratios in excess of 2.0 or even 3.0 for cities like Santa Clara or Palo Alto. We’re less able to fund basic services than those cities because we’re “jobs poor.”

Nonetheless, decades of conversions of employment land — such as industrial, office or retail uses — have worn away our job base.

The political pressures to convert employment-supporting land to housing are tremendous: wealthy developers and development-related industries support local campaigns more than any other funding source. Even surrounding neighborhoods would often rather see an old warehouse or industrial eyesore become redeveloped for more attractive housing and a park.

Accompanying that erosion of our jobs-supporting land has come the erosion of our tax base. I led the task force responsible for crafting San José’s blueprint for future development — known as the General Plan — to hold the line on these conversions, and to focus on a “jobs first” approach.

Of course, housing is still vitally important. Local employers routinely tell us that the lack of reasonably priced housing for their workforce constitutes their greatest impediment to expanding in this Valley. So, we need housing to sustain job growth.

Yet, how we build housing matters. We can focus that new housing development in the form where it provides the best return for our taxpayers: dense development along our key transit corridors, in places like Downtown, along North First Street and near our future BART stations.

For example, I led an effort three years ago to revitalize Downtown housing development by offering basic incentives, such as reducing permit timelines and cutting fees, for high-rise construction in the core. The results — two high-rise residential towers and one hotel under construction, with three more likely to follow in the coming months — will provide a windfall for the General Fund, as we convert blighted parking lots into $130 million towers that will provide millions more in tax revenues annually. This development also provides San José with more environmentally-sustainable “smart growth,” relieving the traffic congestion we’d otherwise see on freeways burdened by suburban sprawl.

For example, I led an effort three years ago to revitalize Downtown housing development by offering basic incentives, such as reducing permit timelines and cutting fees, for high-rise construction in the core. The results — two high-rise residential towers and one hotel under construction, with three more likely to follow in the coming months — will provide a windfall for the General Fund, as we convert blighted parking lots into $130 million towers that will provide millions more in tax revenues annually. This development also provides San José with more environmentally-sustainable “smart growth,” relieving the traffic congestion we’d otherwise see on freeways burdened by suburban sprawl.

As mayor, I’ll push to hold the line against conversions of industrial and other job-supporting parcels, and we’ll focus our housing development on the form that provides the best return for our taxpayers, the least traffic and the least environmental impact. This approach will expand opportunities for growing revenues and jobs that will improve City services, safety and quality of life.

STEP THREE: RESTORE PAY, NOT BENEFITS

As we slowly pull San José’s budget out of its fiscal morass, we’ll need to restore compensation to our employees. Severe cuts — the equivalent of a roughly 14% pay cut, plus sharp increases in required retiree fund contributions, reductions of medical benefits, implementation of a lower-tier pension for new employees and elimination of sick leave pay — have taken their toll on the workforce. Throughout 2012 and 2013, we lost a half-dozen police officers per month, bleeding the department of its experience at a rate far higher than we could possibly hire and train replacements. Defections of electricians to other cities, for example, left us with dangerously low levels of staffing at the sewage plant, forcing us to hire part-time contractors to reduce risks of a shutdown. Neighborhoods wait many months before electricians can address the backlog in repairing streetlights with stolen copper wire.

So, we need to boost compensation to restore our workforce. How we do so, however, remains a critical question.

My view: increase pay, not benefits, to keep people on board. Why? Salary is transparent. Employees know what they’re getting. Taxpayers know what they’re paying. Calculating the cost and value of benefits like pensions and medical insurance is murkier. Their costs depend on a complex interaction of assumptions and actuarial calculations. We might as well be tossing darts at a dartboard.

This murkiness lies at the root of our fiscal problems. Prior to the pension reforms of 2012, councils could avoid appearing as though they were ”selling the store” to politically powerful unions by approving modest increases in pay, but with large improvements in benefits. Why? The costs of those benefits are harder to understand, for the media and the public. Taxpayers get less incensed over a 0.5% increase in an annual pension accrual rate than a 5% increase in pay, yet the former is far costlier than the latter, on a magnitude of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Simply, we have to hold the line against increasing retirement benefits. Financial concessions to unions at the bargaining table should take one form: salary.

While we’re restoring pay, we also need to eliminate those outdated relics of negotiated giveaways that continue to burden taxpayers and the City. Those benefits include the infamous “sick leave payout,” in which some employees can receive six-figure lump-sum payouts upon their retirement, representing the accumulated value of their unutilized sick leave. As of this writing, we’ve eliminated the benefit for most city employees, but the benefit still costs taxpayers millions per year for firefighters. Sick leave was created to help employees take time off to address health problems of their own or their kids, not to pad retirement benefits.

We also have work to do to eliminate overtime pay for those management-level employees who already earn higher salaries by virtue of their elevated position. Although we’ve made progress among our non-public safety employees, we continue to incur seven-figure bills each year for overtime for Fire Battalion Chiefs and supervising officers.

If we cannot eliminate these and other archaic vestiges of our budgetary past, we will lack the money to do what’s most important: to hire more police, pave more streets and keep libraries open to better serve our residents. Nor can we pay employees a sufficient wage to attract the best and brightest. The mayor for San José’s next decade should commit to restoring pay, not capitulate to restoring these “extras.”

CASE STUDY FOR TRANSPARENCY: THE CITY VERSUS THE COUNTY

If the “Rule of Holes” is to stop digging, the way to start is to actually see that you’re standing in one. Sadly, the City’s lack of transparency about its retirement fund deficits in past years left a Council either unaware of, or unwilling to, recognize the depth of the hole. So the City kept digging. The digging stopped in 2012, after the voter-approved pension-reform measure.

Many local municipalities unwittingly continue digging. Residents in other cities and counties have begun to confront their elected officials to ask the same questions we had to ask. Would they open their own closet doors to see what needs to be cleaned? Or, would they continue the path of denial?

We learned the answer in March of 2012, when a group of County Supervisors and local state legislators called a press conference at City Hall to call for a state audit of the City’s pension funds and budget. The timing wasn’t just coincidental; we’d just finished 10 months of contentious negotiations with our labor unions, and remained at an impasse. Unable to reach an agreement, I pushed with a council majority, led by Mayor Reed, to place a measure on the ballot to change the City Charter to overhaul our unsustainable pension system.

The call for an audit was puzzling to many. The City’s actuarial analysis had been vetted months in advance, with little opposition on any technical grounds. Even the police union’s own actuary agreed with the pension fund’s City’s actuary about the size of their pension plan’s multibillion dollar unfunded liabilities. Whatever the critics of Mayor Reed said about his projections of the future size of the pension problem, nobody disagreed about the magnitude of the current problem. In other words, it wasn’t the math we disagreed about; it was how to solve the problem.

Of course, more cynical observers considered the press conference an attempt to slow down the process and avoid a public vote. Indeed, the Mercury News characterized the episode as “a three-ring circus — with the clown imported from Sacramento, where [one] Assemblyman… wants a legislative committee to audit San José’s pension system for purely political purposes.”9

The irony wasn’t lost on many: several of those who indignantly poked their fingers in the air in front of television cameras served on the prior San José city councils that granted these generous retirement benefits. That is, they had their hands on the City’s steering wheel over the prior decades when the pension truck was driven into a $3 billion ditch. Throughout that time, pension boards and city councils cheerily accepted overly optimistic assumptions about the key variables — e.g., the funds’ rates of return, the life expectancies of members and the like — that enabled the City to rack up huge unfunded liabilities.

Of course, the County has pension and retiree healthcare obligations to its own retirees, and questions have long arisen over whether the County has similarly promised more in benefits than it can financially deliver. Decades ago, Santa Clara County actually imposed a special tax on property owners, known as the “PERS Levy,” to help it pay for its pension obligations to the state CalPERS fund. Every one of us who owns a home pays that PERS Levy each year. Even with that tax, the high level of promised benefits left many suspecting that the County’s funds would not suffice to pay its retirement benefits.

When Joe Simitian joined the County Board of Supervisors in early 2013, he’d heard of those suspicions as well. He called for County officials to come clean with the size of their unfunded liabilities. Sure enough, he learned that the County faced some $1.8 billion in unfunded liabilities in its retiree healthcare account alone. When Simitian was last on the County Board, over a decade before, he presided over a liability of only $69 million. Now, after returning from the statehouse, he had the unpleasant experience of being saddled with a problem twenty-five times as large, apparently due to the failure of the County to pay for the benefit for several years. Even worse: the County’s unfunded pension obligations add over $2 billion to that total, making the County’s unfunded liability larger than the City of San José’s.

The public revelations in the media forced County staff to recommend substantially higher retirement contributions from its employees in contract negotiations. Simitian’s efforts to expose these numbers to light, of course, have created a palpable irony: the labor-dominated County Board developed labor problems of its own. Its largest union, SEIU, threatened to strike in August of 2013, objecting to County administration’s insistence that they pay a larger share of their retirement contributions.

There are a few lessons in all of this, but the biggest lies in transparency. Politicians might obfuscate and twist facts, but the numbers don’t lie. None of us — not even the most politically savvy — can hide from the math. Eventually, the public will be forced to foot the bill for shortsighted and politically-motivated decision-making. If we want more responsible budgeting, it all begins by exposing the numbers to the light of day.

5. Don’t Just Think Outside the Box; Destroy the Box

Sometimes our biggest challenge in finding the resources needed to provide a public service lies not in scarcity, but in bureaucratic barriers. In response to a colleague’s repeated use of the overworn admonition to “think outside the box,” Mayor Reed once quipped, “sometimes, we should admit that we created the box.” Where we’ve imposed limitations on our action that have outlived their usefulness, local officials have a responsibility to destroy “the box” in order to get things done.

Sometimes our biggest challenge in finding the resources needed to provide a public service lies not in scarcity, but in bureaucratic barriers. In response to a colleague’s repeated use of the overworn admonition to “think outside the box,” Mayor Reed once quipped, “sometimes, we should admit that we created the box.” Where we’ve imposed limitations on our action that have outlived their usefulness, local officials have a responsibility to destroy “the box” in order to get things done.

As Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley have argued in their recent work, The Metropolitan Revolution, cities provide the rare forum where we can break down boxes to get things done. Congress wallows in partisan gridlock. Powerful lobbyists and interest groups make our state legislature in Sacramento sclerotic, reinforced by politicians who have pledged their fidelity to ideology and party over pragmatic problem solving. So, the challenges fall into the laps of big-city mayors and innovative City Hall thinkers, who increasingly emerge with unorthodox solutions to accomplish goals amid challenging budgetary constraints. We can see a couple of simple examples of that pragmatism right here in San José.

A. HOUSING THE HOMELESS

The unofficial numbers of homeless that live in the dark corners of Santa Clara County streets, creeks and empty lots likely exceed 12,000. For many of them, in addition to their own personal misery, their homelessness carries a large price tag to the public: a single homeless man in San Francisco was estimated to have cost that county’s taxpayers some $60,000 for a single year of emergency medical response, jail visits, police arrests, emergency room visits and the like. Remarkably, it costs about $21,000 annually to house an individual, with the help of a supporting case manager.

Of course, it’s not so simple as to say, “Let’s just house them.” The cost to house all of the County’s homeless has been estimated to exceed half a billion dollars. No public source of funding approaches even a fraction of that amount; annual support for rapid-rehousing strategy for example, approached about 1% of that total.

The best we can do is to be more cost-effective with the scarce dollars that we have. We can start by getting those people who do have some financial resources, such as rental vouchers, into housing. Remarkably, 97 homeless individuals in San José had (at the time of this writing) rental vouchers that would ordinarily entitle them to live in a small apartment, but they cannot find any apartments available at rates resembling what a typical “Section 8” voucher might pay.

Coinciding with the surge in our homeless numbers, we’ve also seen rapid growth in prostitution activity near many of our “motel corridors,” around North 1st Street, Monterrey Road, the Alameda and North 13th Street/Oakland Road, to name a few. We worked with motel owners, many of whom agreed to stop accepting cash payments, to require registration, and to refuse letting rooms to identified pimps. These and multiple other efforts, ranging from undercover police surveillance, to city-filed nuisance lawsuits, to more community-led efforts, have largely failed to get much traction. Prostitution is the world’s oldest profession for a reason, and for every way we could try to stop it from happening, there were three ways around it for persistent pimps, prostitutes and johns.

Many of the motels appeared to have only marginally profitable businesses anyway. I talked to several motel owners who told me that if the City allowed relatively easy re-development or reuse of their buildings, they’d happily get out of the motel business.

So, in 2012, I proposed a relatively simple idea: give owners an incentive to convert them to another use. Specifically, I proposed that we convert run-down motels to affordable housing for the homeless.10 I asked the Housing Department to analyze the option, and they confirmed my suspicions: even for all of the cost of upgrading motel rooms to meet state building codes, we could rehabilitate underutilized motels at a fraction of the cost of constructing new housing. Best of all, we had almost 100 voucher-bearing homeless who could provide the landlord with a steady stream of rental income to help finance the improvements.

After substantial internal wrangling, the Council approved a plan this summer, and we’ll lease up our first motels this year. For hundreds of homeless, this pilot project can provide a promising start on the path to self-sufficiency, while saving taxpayers money.

B. HOW STORM SEWERS CAN PAY TO SWEEP STREETS

When I knocked on doors during my 2006 campaign for City Council, I heard frequent complaints in many modest-income neighborhoods surrounding the Downtown about the lack of street sweeping. “I haven’t seen a street sweeper in a decade,” one Spanish-speaking resident told me. “Todos los calles están sucios!” More affluent neighborhoods rarely had such complaints, though.

Once I got into office, I got to the root the problem: it wasn’t the lack of sweepers; it was too many parked cars. Many homes in our less affluent neighborhoods had multiple families and many adult relatives living under the same roof. As a result, parking was hard to find; all of the residents’ cars filled the street. Most of those neighborhoods lacked signs that would inform residents about the day of the month on which they should expect street sweeping. Given the high proportion of renters in those neighborhoods, often with high turnover in tenancy, few residents knew which day to move their cars. The sweeping machines wouldn’t operate on streets with many parked cars, because the operator didn’t want the liability of damaging the cars with the sweeping equipment. So, the sweeping machine would simply move on — to another street, and too often, to another neighborhood.

Once I got into office, I got to the root the problem: it wasn’t the lack of sweepers; it was too many parked cars. Many homes in our less affluent neighborhoods had multiple families and many adult relatives living under the same roof. As a result, parking was hard to find; all of the residents’ cars filled the street. Most of those neighborhoods lacked signs that would inform residents about the day of the month on which they should expect street sweeping. Given the high proportion of renters in those neighborhoods, often with high turnover in tenancy, few residents knew which day to move their cars. The sweeping machines wouldn’t operate on streets with many parked cars, because the operator didn’t want the liability of damaging the cars with the sweeping equipment. So, the sweeping machine would simply move on — to another street, and too often, to another neighborhood.

The simple solution? Install some street sweeping signs, I urged. Cities like Oakland, San Francisco and Anaheim blanketed their neighborhoods with such signs, covering over 90% of their city streets, to ensure safe passage for street sweepers. In San José, we covered a little more than 8% of our streets. Why couldn’t we perform this simple, inexpensive task?

“Not so fast,” I was told by one Department of Transportation official. “The General Fund runs about $80 million short each year for our annual tab for street paving and maintenance in our city,” they insisted, “and our residents would rather that we prioritize the street repair and repaving over spending dollars on street sweeping signs.” So, street sweeping signs became yet another budgetary casualty. While understandable, it was not defensible that many lower-income residents were still paying (directly, or through their rent, indirectly) a monthly bill that reflected payment for a street sweeping service they never received, all due to the City’s inability to post inexpensive street signs.

While Transportation staff and Council might understandably have defended the General Fund from any additional burden, it seemed to me that we could find funding in another source. I urged us to consider using the Storm Sewer Capital Fund (SSCF).

What does the Storm Sewer fund have to do with street sweeping? Well, it’s a ratepayer-supported fund used to manage and improve storm water runoff — that is, to reduce trash and pollution — to protect our rivers, creeks and the Bay. Street sweeping dramatically reduces the quantity of toxic and nonbiodegradable pollutants — plastic trash, oils and the like — that would reach waterways and damage local habitats. We had millions in the SSCF reserve, with ample funding to pay for routine projects like storm drains and outfalls.

Internally, attorneys objected that state laws created “walls” restricting every fund’s use, and this was an unorthodox way to spend the money. If the use wasn’t “lawful” within the SSCF’s restrictions, a ratepayer could sue the City, and we’d be on the hook. As I came to learn, the fear of getting sued comprised the justification for our failure to accomplish many otherwise sensible objectives in City Hall.

So, with Councilmember Xavier Campos, I took the item to the full Council to have a public discussion over whether the risk of “doing something” was preferable to the certainty of “doing nothing.”11 After extensive analysis, our imminently reasonable City Attorney, Rick Doyle concluded that the expenditure “fit” within the purpose of the fund. New leadership in key city departments (Transportation’s Hans Larsen and Environmental Services’ Kerry Romanow) agreed that we needed a more flexible approach.12 Every councilmember had neighborhoods in need of street sweeping. So, we agreed to break down the “box” that constrained us — and we’re installing hundreds of sweeping signs across miles of neighborhood streets today.

A PARK FOR THE NEWHALL NEIGHBORHOOD

In a small neighborhood just east of The Alameda, local developers and the City had long-promised to convert an empty industrial lot to a park. Neighborhood leaders like John Urban and Matthew Bright had grown tired of hearing of all of the new development planned for the neighborhood — with many families lacking any basic recreational amenities.

In this case, we actually had the money to build the park. The Sobrato Corporation had paid a hefty fee to build a park in the neighborhood as part of its obligations for the construction of a housing development in Newhall. The problem: we had no money to maintain the park.

Developer fees under state law can be used for capital purposes — building parks or playgrounds — but not for operations or maintenance. After the economic collapse in 2008, the Council slashed spending for park maintenance, and the impact was palpable in neighborhood parks citywide. The City was constructing new parks that became overgrown within months, falling into rapid disrepair.